| |

| Bitteersweet Berries Still on the vine in February |

In my last post I started talking about some of the changes that will happen along the bumpy road down and the forces and trends that will lead to them. (The bumpy road down being the cyclic pattern of crash and partial recovery that I believe will characterize the rest of the age of scarcity). These changes will be forced on us by circumstances and are not necessarily how I'd like to see things turn out.

The trends I covered last time were:

- our continued reliance on fossil fuels

- the continuing decline in availability, and surplus energy content, of fossil fuels

- the damage the FIRE industries (finance, insurance and real estate) will suffer in the next crash, and the effects this will have

- the increase in authoritarianism, as governments attempt to optimize critical systems and relief efforts during and after the crash

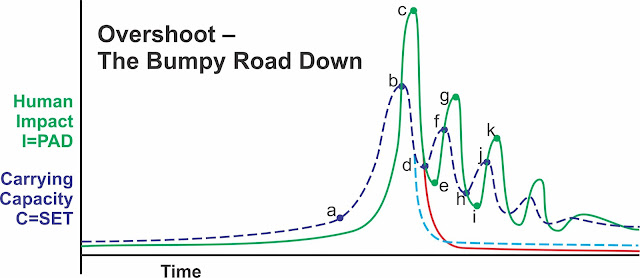

Oscillating overshoot with declining carrying capacity

I've once again included the stepped or "oscillating" decline diagram from previous posts here to make it easier to visualize what I'm talking about. This diagram isn't meant to be precise, certainly not when it comes to the magnitude and duration of the oscillations, which in any case will vary from one part of the world to the next.

The trends I want to talk about today are all interconnected. You can hardly discuss one without referring to the others, and so it is difficult to know where to start. But having touched briefly on a trend toward increased authoritarianism at the end of my last post, I guess I should continue trends in politics.

More Political Trends

Currently there seems to be a trend towards right wing politics in the developed world. I think anyone who extrapolates that out into the long run is making a basic mistake. Where right wing governments have been elected by those looking for change, they will soon prove to be very inept at ruling in an era of degrowth. Following that, there will likely be a swing in the other direction and left wing governments will get elected. Only to prove, in their turn, to be equally inept. Britain seems to be heading in this direction, and perhaps the U.S. as well.

Another trend is the sort of populism that uses other nations, and/or racial, ethnic, religious and sexual minorities at home as scapegoats for whatever problems the majority is facing. This strategy is and will continue to be used by clever politicians to gain support and deflect attention from their own shortcomings. Unfortunately, it leads nowhere since the people being blamed aren't the source of the problem.

During the next crash and following recovery governments will continue to see growth as the best solution to whatever problems they face and will continue to be blind to the limits to growth. Farther down the bumpy road some governments may finally clue in about limits. Others won't, and this will fuel continued growth followed by crashes until we learn to live within those limits.

One thing that seems clear is that eventually we'll be living in smaller groups and the sort of political systems that work best will be very different from what we have now.

Many people who have thought about this assume that we'll return to feudalism. I think that's pretty unlikely. History may seem to repeat itself, but only in loose outline, not in the important details. New situations arise from different circumstances, and so are themselves different. Modern capitalists would never accept the obligations that the feudal aristocracy had to the peasantry. Indeed freeing themselves of those obligations had a lot to do with making capitalism work. And the "99%" (today's peasantry) simply don't accept that the upper classes have any right, divine or otherwise, to rule.

In small enough groups, with sufficient isolation between groups, people seem best suited to primitive communism, with essentially no hierarchy and decision making by consensus. I think many people will end up living in just such situations.

In the end though, there will still be a few areas with sufficient energy resources to support larger and more centralized concentrations of population. It will be interesting to see what new forms of political structure evolve in those situations.

Economic Contraction

For the last couple of decades declining surplus energy has caused contraction of the real economy. Large corporations have responded in various ways to maintain their profits: moving industrial operations to developing countries where wages are lower and regulations less troublesome, automating to reduce the amount of expensive labour required, moving to the financial and information sectors of the economy where energy decline has so far had less effect.

The remaining "good" industrial jobs in developed nations are less likely to be unionized, with longer hours, lower pay, decreased benefits, poorer working conditions and lower safety standards. The large number of people who can't even get one of those jobs have had to move to precarious, part time, low paying jobs in the service industries. Unemployment has increased (despite what official statistics say) and the ranks of the homeless have swelled.

Since workers are also consumers, all this has led to further contraction of the consumer economy. We can certainly expect to see this trend continue and increase sharply during the next crash.

Our globally interconnected economy is a complex thing and that complexity is expensive to maintain. During the crash and the depression that follows it, we'll see trends toward simplification in many different areas driven by a lack of resources to maintain the existing complex systems. I'll be discussing those trends in a moment, but it is important to note that a lot of economic activity is involved in maintaining our current level of complexity and abandoning that complexity will mean even more economic contraction.

At the same time, small, simple communities will prove to have some advantages that aren't currently obvious.

Conservation

All this economic contraction means that almost all of us will be significantly poorer and we'll have to learn to get by with less. As John Michael Greer says, "LESS: less energy, less stuff, less stimulation." We'll be forced to conserve and will struggle to get by with "just enough". This will be a harshly unpleasant experience for most people.

Deglobalization

For the last few decades globalization has been a popular trend, especially among the rich and powerful, who are quick to extol its many supposed advantages. And understandably so, since it has enabled them to maintain their accustomed high standard of living while the economy as a whole contracts.

On the other hand, as I was just saying, sending high paying jobs offshore is a pretty bad idea for consumer economies. And I suspect that in the long run we'll see that it wasn't really all that good for the countries where we sent the work, either.

During the crash we'll see the breakdown of the financial and organizational mechanisms that support globalization and international trade. There will also be considerable problems with shipping, both due to disorganization and to unreliable the supplies of diesel fuel for trucks and bunker fuel for ships. I'm not predicting an absolute shortage of oil quite this soon, but rather financial and organizational problems with getting it out of the ground, refined and moved to where it is needed.

This will lead to the failure of many international supply chains and governments and industry will be forced to switch critical systems over to more local suppliers. This switchover will be part of what eventually drives a partial recovery of the economy in many localities.

In a contracting economy with collapsing globalization there would seem to be little future for multi-national corporations, and organizations like the World Bank and the IMF. While the crash may bring an end to the so called "development" of the "developing" nations, it will also bring an end to economic imperialism. At the same time, the general public in the developed world, many of whom are already questioning the wisdom of the "race to the bottom" that is globalization, will be even less likely to go along with it, especially when it comes to exporting jobs.

Still, when the upcoming crash bottoms out and the economy begins to recover, there will be renewed demand for things that can only be had from overseas and international trade will recover to some extent.

Decentralization

Impoverished organizations such a governments, multi-national corporations and international standards groups will struggle to maintain today's high degree of centralization and eventually will be forced to break up into smaller entities.

Large federations such as Europe, the US, Canada and Australia will see rising separatism and eventually secession. As will other countries where different ethnic groups have been forced together and/or there is long standing animosity between various localities. If this can be done peacefully it may actually improve conditions for the citizens of the areas involved, who would no longer have to support the federal organization. But no doubt it will just as often involve armed conflict, with all the destruction and suffering that implies.

Relocalization

The cessation of services from the FIRE industries and the resulting breakdown of international (and even national) supply and distribution chains will leave many communities with no choice but to fend for themselves.

One of the biggest challenges at first will be to get people to believe that there really is a problem. Once that is clear, experience has shown that the effectiveness of response from the victims of disasters is remarkable and I think that will be true again in this case. There are a lot of widely accepted myths about how society breaks down during disaster, but that's just what they are: myths. Working together in groups for our mutual benefit is the heart of humanity's success, after all.

Government response will take days or more likely weeks to organize, and in the meantime there is much we can do to help ourselves. Of course it helps to be prepared... (check out these posts from the early days of this blog: 1, 2) and I'll have more to say on that in upcoming posts.

The question then arises whether one would be better off in an urban center or a rural area such as a small town or a farm. Government relief efforts will be focused on the cities where the need will be greatest and the response easiest to organize. But just because of the millions of people involved, that response will be quite challenging.

Rural communities may well be largely neglected by relief efforts. But, especially in agricultural areas, they will find fending for themselves much more manageable.

I live in a rural municipality with a population of less than 12,000 people in an area of over 200 square miles (60 people per sq. mile, more than 10 acres per person). The majority of the land is agricultural, and supply chains are short, walking distance in many cases. Beef, dairy and cash crops are the main agricultural activities at present and they can easily be diverted to feed the local population. Especially if the food would go to waste anyway due to the breakdown of supply chains downstream from the farm.

So I think we're likely to do fairly well until the government gets around to getting in touch with us again, probably sometime after the recovery begins.

In subsequent crashes the population will be significantly reduced and those of us who survive will find ourselves living for the most part in very small communities which are almost entirely relocalized. The kind of economy that works in that situation is very different from what we have today and is concerned with many things other than growth and profit making.

Rehumanization

The move toward automation that we've seen in the developed world since the start of the industrial revolution has been driven by high labour costs and the savings to be had by eliminating labour from industrial processes as much as possible. That revolution started and proceeded at greatest speed in Britain where labour rates where the highest, and still hasn't happened in many developing nations where labour is very cheap.

Sadly, the further impoverishment of the working class in Europe and North American will make cheaper labour available locally, rather than having to go offshore. During the upcoming crash, and in the depression following it, impoverished people will have no choice but to work for lower rates and will out compete automated systems, especially when capital to set them up, the cutting edge technology needed to make them work, and the energy to power them are hard to come by. Again, the economic advantages of simplicity will come into play when it is the only alternative, and help drive the recovery after the first crash.

The Food Supply and Overpopulation

In the initial days of the coming crash there will be problems with the distribution systems for food, medical supplies and water treatment chemicals, all of which are being supplied by "just in time" systems with very little inventory at the consumer end of the supply chain. To simplify this discussion, I'll talk primarily about food.

It is often said that there is only a 3 day supply of food on the grocery store shelves. I am sure this is approximately correct. In collapse circles, the assumption is that, if the trucks stop coming, sometime not very far beyond that 3 day horizon we'd be facing starvation. There may be a few, incredibly unlucky, areas where that will be more or less true.

But, depending on the time of year, much more food than that (often more than a year's worth) is stored elsewhere in the food production and distribution system. The problem will be in moving this food around to where it is needed, and in making sure another year's crops get planted and harvested. I think this can be done, much of it through improvisation and co-operation by people in the agricultural and food industries. With some support from various levels of government.

There will be some areas where food is available more or less as normal, some where the supply is tight, and other areas where there is outright famine and some loss of life (though still outstripped by the fecundity of the human race). In many ways that pretty much describes the situation today but supply chain breakdown, and our various degrees of success at coping with it, will make all the existing problems worse during the crash.

But once the initial crash is over, we have a much bigger problem looming ahead, which I think will eventually lead to another, even more serious crash.

With my apologies to my "crunchy" friends, modern agriculture and the systems downstream from it supply us with the cheapest and safest food that mankind has known since we were hunters and gatherers and allows us (so far) to support an ever growing human population.

The problem is that this agriculture is not sustainable. It requires high levels of inputs--primarily energy from fossil fuels, but also pesticides, fertilizers and water for irrigation--mostly from non-renewable sources. And rather than enriching the soil on which it depends, it gradually consumes it, causing erosion from over cultivation and over grazing, salinating the soil where irrigation is used and poisoning the water courses downstream with runoff from fertilizers. We need to develop a suite of sustainable agricultural practices that takes advantage of the best agricultural science can do for us, while the infrastructure that supports that science is still functioning.

The organic industry spends extravagantly to convince us that the problem with our food is pesticide residues and genetically engineered organisms, but the scientific consensus simply does not support this. The organic standards include so called "natural" pesticides that are more toxic than modern synthetic ones, and allow plant breeding techniques (such as mutagenesis) that are far more dangerous than modern genetic engineering. Organic standards could certainly be revised into something sustainable that retains the best of both conventional and organic techniques, but this has become such a political hot potato that it is unlikely to happen.

As I said above, during the upcoming crash one of the main challenges will be to keep people fed. And I have no doubt that this challenge will, for the most part, be successfully met. Diesel fuel will be rationed and sent preferentially to farmers and trucking companies moving agricultural inputs and outputs. Supplies of mineral fertilizers are still sufficient to keep industrial agriculture going. Modern pesticides actually reduce the need for cultivation and improve yields by reducing losses due to pests. It will be possible to divert grains grown for animal feed to feed people during the first year when the crisis is most serious.

Industrial agriculture will actually save the day and continue on to feed the growing population for a while yet. We will continue to make some improvement in techniques and seeds, though with diminishing returns on our efforts.

This will come to an end around mid century with the second bump on the road ahead (starting at point "g" on the graph), when a combination of increasing population, worsening climate, and decreasing availability and increasing prices of energy, irrigation water, fertilizer, pesticides and so forth combine to drastically reduce the output of modern agriculture.

Widespread famine will result, and this, combined with epidemics in populations weakened by hunger, will reduce the planet's human population by at least a factor of two in a period of a very few years. Subsequent bumps as climate change further worsens conditions for farming will further reduce the population, resulting in a bottleneck towards the end of this century. Without powered machinery, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and with drastically reduced water for irrigation, agricultural output will fall off considerably. And our population will fall to match the availability of food. I do think it unlikely that the human race will be wiped out altogether, but our numbers will likely be reduced by a factor of ten or more.

Turning to Violence as a Solution

It is a sad fact that many people, communities and nations, when faced with the sort of challenges I've been talking about here, will respond with violence.

In the remaining years leading up to the next crash, I think it is likely that even the least stable of world leaders (or their military advisors) will remain well aware of the horrific consequences of large scale nuclear war, and will manage to avoid it. As has been the case since the end of WWII, wars will continue to be fought by proxy, involving smaller nations in the developing world, especially where the supply of strategic natural resources are at issue.

War is extremely expensive though and, even without the help of a financial crash, military spending already threatens to bankrupt the U.S. As Dmitry Orlov has suggested, after a financial crash, the U.S. may find it difficult to even get its military personnel home from overseas bases, much less maintain those bases or pursue international military objectives.

But even in the impoverished post-crash world, I expect that border wars, terrorism, riots and violent protests will continue for quite some time yet.

Migration and Refugees

Whether from the ravages of war, climate change or economic contraction many areas of the world, particularly in areas like the Middle East, North Africa and the U.S. southwest, will become less and less livable. People will leave those areas looking for greener pastures and the number of refugees will soon grow past what can be managed even by the richest of nations. This will be a problem for Europe in particular, and more and more borders will be closed to all but a trickle of migrants. Refugees will accumulate in camps and for a while the situation will find an uneasy balance.

As we continue down the bumpy road, though, many nations will lose the ability to police their borders. Refugees will pour through, only to find broken economies that offer them little hope of a livelihood. Famine, disease and conflict will eventually reduce the population to where it can be accommodated in the remaining livable areas. But the ethnic makeup of those areas will have changed significantly due to large scale migrations.

In Conclusion

I've been talking here about some of the changes that will be forced upon us by the circumstances of collapse. I've said very little about what I think we might do if we could face up to the reality of those circumstances and take positive action. That's because I don't think there is much chance that we'll take any such action on a global or even national scale.

It's time now to wrap up this series of posts about the bumpy road down. At some point in the future I intend to do a series about of coping with collapse locally, on the community, family and individual level. I think there is still much than can be done to improve the prospects of those who are willing to try.

Links to the rest of this series of posts:

Political Realities / Collapse Step by Step / The Bumpy Road Down

- Collapse Step-by-Step, Part 1: Unevenly, Unsteadily and Unequally , Tuesday, 23 May 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 2: End Points, Friday, 16 June 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 3: Political Compasses , Saturday, 29 July 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 4: Political Positions, Sunday, 6 August 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 5: Political Realities, Wednesday, 30 August 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 6: More on Political Realities, Monday, 9 October 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 7: More on Political Realities, Continued, Friday, 13 October 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 8--The Bumpy Road Down, Part 1, Sunday, 26 November 2017

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 2, Sunday, 7 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 3, Monday, 15 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 4: Trends in Collapse, Friday, 26 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 5: More Trends in Collapse, Tuesday, 20 February 2018

7 comments:

Irv, I think I touched on most of these issues in After the Last Day. Of course, my timescales are compressed for story reasons, but it is hard to predict the timing anyway, as you point out. You have more faith in the goodwill and effectiveness of governments than I have. In any event, the bumpiness will not be evenly distributed in both time and space so it is impossible to predict precisely for any region, country or locality. Availability of energy will be a big determining factor. I made sure I put the disclaimer at the front of my story that it is neither a prediction or a how-to book. I eliminate about 80% of the local population and perhaps your 90% is closer to what will eventually happen. My purpose in writing the story was hoping to reach those who will not read non-fiction discussion such as this blog. In the follow-up story, The Seventh Path, I introduce a locality that is industrial and expansionist, 150 years after my collapse. The sequel to that will discuss the details and what will be the inevitable failure of the effort. The bumpiness will continue for some time.

"In small enough groups, with sufficient isolation between groups, people seem best suited to primitive communism, with essentially no hierarchy and decision making by consensus. I think many people will end up living in just such situations."

And the reason for that is that it works. It's how humans evolved to live. We are simply not adapted to live the way we do and the evidence is all around us, if only the majority of us could see it.

Thanks for another great post. I look forward to the next series.

Would be curious as to what the stabilization might look like.

@Don Hayward

I am reading After the Last Day and enjoying it. And I'm not about to quibble about the details of how you have things proceeding. Seeing it laid out like that, I find it quite helpful to thinking about what might happen and how to respond.

I think I do have more faith than some in the government and in individuals in big companies taking action to keep things going. But you've been quite generous to Hydro One and without saying it, to Ontario Power Generation as well, who are quietly keeping the generating stations going in the background of your story.

I especially like the way you have the people in Weyburne getting together co-operatively and taking care of themselves. Most people these days don't give that sort of thing enough credit.

@foodnstuff

Thanks, Bev, you've got it right how humans evolved to live. I may be too optimistic about modern people being able to learn to live that way again, but I think we can.

@Eric

I didn't bring that together in one place, though I think I dropped a lot of hints, both in this post and in some of the earlier ones. And remember that "the balance of nature" is a myth, so the idea of there being such a thing as a long term stable state is not really realistic.

Having said that, I am for some strange reason tempted to take a preliminary run at answering your question, with a long range plan of writing a post on this subject sometime this year.

For us to get to a stable state, the one time energy bonanza of fossil fuels has to be over. This is not to say that there will be no fossil fuels left in the ground, but rather that it will take as much or more energy to get them out of the ground than they provide once we get them out. EROEI<=1. Our energy sources will be the sun and indirect solar sources like biomass, falling water and the wind. Maybe waves and tides (and yes, I know tides aren't solar energy). The EROEI of these energy sources will average out to around 10, ranging from around 5 to not much more than 15.

The next element in a stable state would be that climate change is essentially over. The CO2 we added to the air burning fossil fuels will have been taken back out by biological processes, and damaged ecosystems, on land, but more importantly in the oceans, will have recovered to the extent they are going to recover. I suspect that the deserts will have grown and there will be fewer ideal human habitat than there are now.

This will be the age of salvage. The remnants of modern civilization, especially refined metals, will around for a long time and even hunter gatherers (who there will be more of) will have iron tools.

The majority of us will still be engaged in some sort of agriculture. Here rain is a major determining factor.

If rain comes to us indirectly via a river and has to be applied to the filed via some sort of irrigation infrastructure, then the infrastructure has to be built, operated and maintained. This requires a central authority and lots of people who operate under the close control of that authority. Not the most pleasant sort of society, in my opinion. The kind of place where that control can become too oppressive and heading for the hills becomes an option that people are eager to take.

If rain falls where it is needed (on our fields) you get a much less centralized society where farmers are more independent.

There are a few exceptions like the pacific northwest and a variety of fertile river valleys/deltas where the forests, rivers, and the ocean provide abundantly for people with relatively little agriculture, technology or organization.

In those exceptional cases where an abundance of falling water makes a higher level of energy available, even the possibility of generating electricity, this will support a a higher level of technology.

I hesitate to make statements like having a society at level similar to some point in our past because then people will jump to all kinds of conclusion about details, which I don't think are supported. But if we can restrict that to just the amount of energy that is available per capita, then I think most people will be living at a 17th century level at best. Pre-fossil fuels and pre-electricity.

If there is a supply of falling water in the area, and large forests, then it might even get up to early 20th century, but of course without fossil fuels.

We'll at this point I think there is probably much more to say, but I have run out of steam for the night.

Looking forward to your future posts on individual and community methods of preparing for collapse. Whether collapse to 17th century energy levels is direct and rapid or undulating and takes decades, preparation will be generally the same. Prudence would also suggest preparing for the worst-case scenario, which would be rapid collapse.

Post a Comment