|

| Bamboo in Winter |

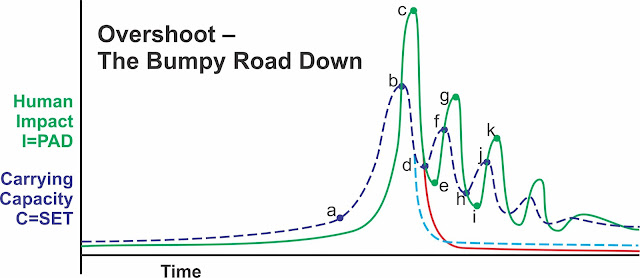

This time I'm going to look at some of the changes that will happen along the bumpy road down and the forces and trends that will lead to them. If you followed what I was saying in my last post, you'll have realized that the bumpy road will be a matter of repeatedly getting slapped down as a result of going into overshoot—exceeding our limits, crashing, then recovering, only to get slapped again as we go into overshoot yet again.

Along the way, where people have a choice, they will choose to do a range of different things (some beneficial, others not so much), according to their circumstances and inclinations. Inertia is also an important factor—people resist change. And politicians are adept at "kicking the can down the road"—patching together the current system to keep it working for little while longer and letting the guy who gets elected next worry about the consequences.

Because the world will become a smaller place for most of us, we'll feel less influence from other areas and in turn have less influence over them. There will be a lot more "dissensus"—people doing their own thing and letting other people do theirs. I expect this will lead to quite a variety of approaches, some that fail and some that do work to some extent. In the short run, of course, "working" means recovering from whatever disaster we are currently trying to cope with. But in the long run, the real challenge is learning to live within our limits and accept "just enough" rather than always striving for more. Trying a lot of different approaches to this will make it more likely that we find some that are successful.

Anyways—changes, forces and trends...and how they will work on the bumpy road down.

I've included the stepped or "oscillating" decline diagram from my last post here to make it easier to visualize what I'm talking about.

Energy Decline

Because I'm a "Peak Oil guy" and because energy is at the heart of the financial problems we're facing, I'll talk about energy first. As I said in a recent post:

"Despite all the optimistic talk about renewable energy, we are still dependent on fossil fuels for the great majority of our energy needs, and those needs are largely ones that cannot be met by anything other than fossil fuels, especially oil. While it is true that fossil fuels are far from running out, the amount of surplus energy they deliver (the EROEI—energy returned on energy invested) has declined to the point where it no longer supports robust economic growth. Indeed, since the 1990s, real economic growth has largely stopped. What limited growth we are seeing is based on debt, rather than an abundance of surplus energy."

It is my analysis that there is zero chance of implementing any alternative to fossil fuels remotely capable of sustaining "business as usual" in the remaining few years before a major economic crash happens and changes everything. So the first trend I'll point to is a continued reliance on fossil fuels. Fuels of ever decreasing EROEI, which will increase the stress on the global economy and continue contributing to climate change and ocean acidification.

Those who are mainly concerned about the environmental effects of continuing to burn fossil fuels would have us stop using those fuels, whatever the cost. But it is clear to me that the cost of such a move would be a global economic depression different only in the details from the one I've been predicting. Lack of energy, excess of debt, environmental disaster—take your pick....

It has been interesting to watch the governments of Canada and the US take two different approaches to this over the last couple of years.

The American approach has been based on denial. Denial of climate change on the one hand, and denial of the fossil fuel depletion situation on the other. "Drill baby, drill!" is expected to solve the energy problem without causing an environmental problem. I don't believe that either expectation will be borne out over the next few years.

Our Canadian government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has made quite a bit of political hay by acknowledging the reality of climate change and championing the Paris Climate Agreement in the international arena. Here at home, though, it is clear that Trudeau understands the role of oil in our economy and he has been quick to quietly reassure the oil companies that they have nothing to fear, approving two major pipeline projects to keep oil flowing from Alberta to the Pacific coast and, eventually, to Chinese markets.

Yes, Ottawa has set a starting price of $10 a tonne on carbon dioxide emissions in 2018, increasing to $50 a tonne by 2022. This is to be implemented by provincial governments who have until the end of the year to submit their own carbon pricing plans before a national price is imposed on those that don't meet the federal standard. It will be interesting to see how this goes and if the federal government sticks to its plan. Canada is one of the most highly indebted nations in the world and I wouldn't be surprised if our economy was one of the first to falter.

At any rate, sometime in the next few years the economy is going to fall apart (point "c" in the diagram). As I've said, this may well be initiated by volatility in oil prices as the current oil surplus situation comes to an end. This will lead to financial chaos that soon spreads to the rest of the economy.

On the face of it this isn't too different from the traditional Peak Oil scenario—the collapse of industrial civilization caused by oil shortages and sharply rising oil prices. But as you might guess by now, this isn't exactly what I think will happen.

In fact, I think that we'll see an economic depression where the demand for oil drops more quickly than the natural decline rate of our oil supplies and the price falls even further than it did in 2014-15. We won't be using nearly so much oil as at present, so we will once again accumulate a surplus, and we'll even leave some reserves of oil in the ground, at least initially. This will help drive a recovery after the depression bottoms out (point "e" in the diagram). Please note that I am talking about the remaining relatively high EROEI conventional oil here. Unconventional sources just don't produce enough surplus energy to fuel a recovery.

But the demand for oil will still be a lot less than it is today and this will have a very negative effect on oil companies. Some governments will subsidize the oil industry even more than they have traditionally, just to keep to it going in the face of low prices. Other governments will outright nationalize their oil industries to ensure oil keeps getting pumped out of the ground, even if it isn't very profitable to do so. Bankruptcy of critical industries in general is going to be a problem during and after the crash. More on that in my next post.

During the upcoming crash and depression fossil fuel use may well decline enough to significantly reduce our releases of CO2 into the atmosphere—not enough perhaps to stop climate change, but enough to slow it down. As we continue down the bumpy road, though, our use of fossil fuels and the release of CO2 from burning them will taper off to essentially nothing, allowing the ecosphere to finally begin a slow recovery from the abuses of the industrial age.

The other trend involving fossil fuels, as we go further down the bumpy road, will be their declining availability as we gradually use them up. Eventual our energy consumption will be determined by the local availability of renewable energy that can be accessed using a relatively low level of technology. Things like biomass (mainly firewood), falling water, wind, passive solar, maybe even tidal and wave energy. Since these sources vary in quantity from one locality to another, the level of energy use will vary as well. Where these sources are intermittent, the users will simply have adapt to that intermittency.

No doubt some of my readers will be wondering why I don't think high tech renewables like solar cells and large wind turbines will save the day. The list of reasons is a long one—difficulty raising capital in a contracting economy, low EROEI, intermittency of supply and the difficulty (once fossil fuels are gone) of building, operating, maintaining and replacing such equipment when is wears out—to mention just a few.

Large scale storage of power to deal with intermittency will in the long run prove infeasible. Certainly batteries aren't going to do it. There are a few locations where pumped storage of water can be set up at a relatively low cost, but not enough to make a big difference. And on top of all that, I very much doubt that large electrical grids are feasible in the long run (and I spent half my life maintaining on one such grid).

The FIRE Industries

The next trend I can see is in the FIRE (financial, insurance and real estate) sector of the economy. During the growth phase of our economy over that last couple of centuries the FIRE industries embodied a wide range of organizational technologies that facilitated business, trade and growth. Unfortunately, because they were set up to support growth, they were unable to cope with the end of real growth late in the twentieth century. They have supported debt based growth for the last couple of decades as the only alternative that they could deal with. This led to the unprecedented amount of debt that we see in the world today. Much of this debt is quite risky and will likely lead to a wave of bankruptcies and defaults—the very crash I've been talking about.

The FIRE industries will be at the heart of that crash and will suffer horribly. Many, perhaps the majority, of the companies in that sector won't survive. In today's world they wield a great deal of political power. During the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007-8 that power was enough to see them through largely unscathed. This is unlikely to be the case in the upcoming crash, creating a desperate need for their services and an opportunity to fill that need which will be another factor in the recovery after the crash bottoms out. But of course there is more than one way it can be done.

In the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th posts in my " Collapse Step by Step" series, I dealt with the political realities of our modern world, which limit what can be done by democratic governments. I identified a political spectrum defined by those limits. At the left end of this spectrum we have Social Democratic societies, which still practice capitalism, but where those in power are concerned with the welfare of everyone within the society. At the right end we have Right Wing Capitalist societies where the ruling elite is concerned only with accumulating more wealth and power for itself.

Since the FIRE industries are crucial to the accumulation and distribution of wealth in our societies, the way they are rebuilt following the crash will be largely determined by the political goals of those doing the rebuilding.

At the left end of the spectrum there is much can be done to regulate the FIRE industries and stop their excesses from leading immediately to further crises.

At the right end of the political spectrum the elite is so closely tied to the FIRE industries and so little concerned with the welfare of the general populace, that those industries will likely be rebuilt on a plan very similar to their current organization. A policy of "exterminism" is likely to be followed, where prosperity for the elite and an ever shrinking middle class is seen as the only goal and the poor are a burden to be abandoned or outright exterminated.(Thanks for Peter Frase, author of Four Futures—Life After Captialism for the term "exterminism".)

In the case of either of these extremes, or anywhere along the spectrum between them, there are some common things I can see happening.

The whole FIRE sector depends on trust. In the last few decades (since the 1970s) we have switched from currencies based on precious metals to "fiat money" which is based on nothing but trust in the governments issuing it. This was done to accommodate growth fueled by abundant surplus energy and then to facilitate issuing ever more debt as the surplus energy supply declined. I don't advocate going back to precious metals—what we need is a monetary system that can accommodate degrowth, of which a great deal lies in our future. Unfortunately we don't yet know what such a system might look like.

It is clear, though, that the coming crash is going to shake our trust in the FIRE industries to its very roots. Since central banks will have been central to the monetary problems leading to the crash, they may well be set up as scapegoats for that crash and their relative lack of success in coping with it. People will be very suspicious after watching the FIRE industries fall apart during the crash and their lack of trust will force those industries to take some different approaches.

I think governments will take over the functions of central banks and stop charging themselves interest on the money they print. Yes, I know that printing money has often led to runaway inflation, but the conditions during the crash and its aftermath will be so profoundly deflationary that inflation will not likely be a problem.

The creation of debt will be viewed much less favourably and credit will be much harder to get. And of course this will make the crash and following depression that much worse. In response to this many areas will create local banks and currencies to provide the services and credit that local businesses need to get moving again.

During the last couple of decades there has been a move to loosen regulations in the FIRE industries, to let single large entities become involved in investment banking, business and personal banking, insurance and real estate. Most such entities began as experts in one of those areas, but one has to question their expertise in the new areas they moved into. In any case they became "too big to fail" and their failure threatened the stability the whole FIRE sector. Following the GFC there was only minor tightening of regulations to discourage this sort of thing. After the upcoming crash I suspect many governments, especially toward the left end of the political spectrum, will institute a major re-regulation of the FIRE industries and a splitting up of the few "too big to fail" companies which didn't actually fail.

It is all very well to talk about business and even governments failing when their debt load becomes too great. But there is also a lot of personal debt that is, at this point, unlikely ever to get paid back. What does it mean, in this context, for a person to fail? What I carry as debt is an asset for someone else—probably the share holders of a bank. They are understandably reluctant to watch their assets evaporate, and I have to admit that there is a moral hazard involved in just letting people walk away from their debts. That feeling was so strong in the past that those who couldn't pay their debts ended up in debtors' prisons. Such punishment was eventually seen as futile and the practice was abandoned and personal bankruptcies were allowed.

One suspects that in the depression following the coming crash it will be necessary to declare a jubilee, forgiving large classes of personal debt. What might become of all the suddenly destitute people depends on where their country lies on the political spectrum. I wouldn't rule out debtors prisons or work camps, the sort of modern slavery that is already gaining a foothold in the prison system of the United States.

If we were willing to give up growth as the sole purpose of our economic system, there are many changes that could be made to the FIRE industries that would allow them to provide the services needed by businesses and individuals without stimulating the unchecked growth that leads to collapse. I think we are unlikely to see this happen after the upcoming crash—we will be desperate for recovery and that will still mean growth at destructive levels.

I think the crash following that recovery will involve the food supply and still unchecked population growth and sadly a lot of people won't make it through (more on this in my next post). Following that, it's even possible that in some areas people may reach the conclusion that growth is the problem and quit sticking their heads up to get slapped down again. They'll have to find a more sustainable way to live, but with it will come a less bumpy road forward.

Authoritarianism

In the aftermath of the next crash, I think we'll see an increase in authoritarianism in an attempt to optimize the systems that failed during the crash—to make them work again and work more effectively. Free market laissez faire economics will be seen to have failed by many people. Others will hang tight, claiming that if they just keep doing yet again the same thing that failed before, it will finally work.

As is always the case with this sort of optimization, it will create a less resilient system, much more susceptible to subsequent crashes. And after those crashes government will be reduced to such a small scale affair that authoritarianism won't be so much of an issue.

Fortunately, beyond authoritarianism, there are some other trends that will lead to increased resilience and sustainability. We'll take a look at those in my next post.

Links to the rest of this series of posts:

Political Realities / Collapse Step by Step / The Bumpy Road Down

- Collapse Step-by-Step, Part 1: Unevenly, Unsteadily and Unequally , Tuesday, 23 May 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 2: End Points, Friday, 16 June 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 3: Political Compasses , Saturday, 29 July 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 4: Political Positions, Sunday, 6 August 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 5: Political Realities, Wednesday, 30 August 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 6: More on Political Realities, Monday, 9 October 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 7: More on Political Realities, Continued, Friday, 13 October 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 8--The Bumpy Road Down, Part 1, Sunday, 26 November 2017

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 2, Sunday, 7 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 3, Monday, 15 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 4: Trends in Collapse, Friday, 26 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 5: More Trends in Collapse, Tuesday, 20 February 2018