|

| Bamboo in Winter |

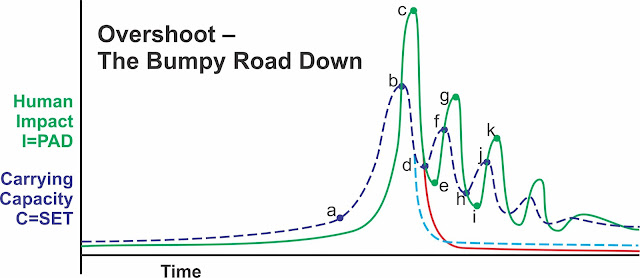

This time I'm going to look at some of the changes that will happen along the bumpy road down and the forces and trends that will lead to them. If you followed what I was saying in my last post, you'll have realized that the bumpy road will be a matter of repeatedly getting slapped down as a result of going into overshoot—exceeding our limits, crashing, then recovering, only to get slapped again as we go into overshoot yet again.

Along the way, where people have a choice, they will choose to do a range of different things (some beneficial, others not so much), according to their circumstances and inclinations. Inertia is also an important factor—people resist change. And politicians are adept at "kicking the can down the road"—patching together the current system to keep it working for little while longer and letting the guy who gets elected next worry about the consequences.

Because the world will become a smaller place for most of us, we'll feel less influence from other areas and in turn have less influence over them. There will be a lot more "dissensus"—people doing their own thing and letting other people do theirs. I expect this will lead to quite a variety of approaches, some that fail and some that do work to some extent. In the short run, of course, "working" means recovering from whatever disaster we are currently trying to cope with. But in the long run, the real challenge is learning to live within our limits and accept "just enough" rather than always striving for more. Trying a lot of different approaches to this will make it more likely that we find some that are successful.

Anyways—changes, forces and trends...and how they will work on the bumpy road down.

I've included the stepped or "oscillating" decline diagram from my last post here to make it easier to visualize what I'm talking about.

Energy Decline

Because I'm a "Peak Oil guy" and because energy is at the heart of the financial problems we're facing, I'll talk about energy first. As I said in a recent post:

"Despite all the optimistic talk about renewable energy, we are still dependent on fossil fuels for the great majority of our energy needs, and those needs are largely ones that cannot be met by anything other than fossil fuels, especially oil. While it is true that fossil fuels are far from running out, the amount of surplus energy they deliver (the EROEI—energy returned on energy invested) has declined to the point where it no longer supports robust economic growth. Indeed, since the 1990s, real economic growth has largely stopped. What limited growth we are seeing is based on debt, rather than an abundance of surplus energy."

It is my analysis that there is zero chance of implementing any alternative to fossil fuels remotely capable of sustaining "business as usual" in the remaining few years before a major economic crash happens and changes everything. So the first trend I'll point to is a continued reliance on fossil fuels. Fuels of ever decreasing EROEI, which will increase the stress on the global economy and continue contributing to climate change and ocean acidification.

Those who are mainly concerned about the environmental effects of continuing to burn fossil fuels would have us stop using those fuels, whatever the cost. But it is clear to me that the cost of such a move would be a global economic depression different only in the details from the one I've been predicting. Lack of energy, excess of debt, environmental disaster—take your pick....

It has been interesting to watch the governments of Canada and the US take two different approaches to this over the last couple of years.

The American approach has been based on denial. Denial of climate change on the one hand, and denial of the fossil fuel depletion situation on the other. "Drill baby, drill!" is expected to solve the energy problem without causing an environmental problem. I don't believe that either expectation will be borne out over the next few years.

Our Canadian government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has made quite a bit of political hay by acknowledging the reality of climate change and championing the Paris Climate Agreement in the international arena. Here at home, though, it is clear that Trudeau understands the role of oil in our economy and he has been quick to quietly reassure the oil companies that they have nothing to fear, approving two major pipeline projects to keep oil flowing from Alberta to the Pacific coast and, eventually, to Chinese markets.

Yes, Ottawa has set a starting price of $10 a tonne on carbon dioxide emissions in 2018, increasing to $50 a tonne by 2022. This is to be implemented by provincial governments who have until the end of the year to submit their own carbon pricing plans before a national price is imposed on those that don't meet the federal standard. It will be interesting to see how this goes and if the federal government sticks to its plan. Canada is one of the most highly indebted nations in the world and I wouldn't be surprised if our economy was one of the first to falter.

At any rate, sometime in the next few years the economy is going to fall apart (point "c" in the diagram). As I've said, this may well be initiated by volatility in oil prices as the current oil surplus situation comes to an end. This will lead to financial chaos that soon spreads to the rest of the economy.

On the face of it this isn't too different from the traditional Peak Oil scenario—the collapse of industrial civilization caused by oil shortages and sharply rising oil prices. But as you might guess by now, this isn't exactly what I think will happen.

In fact, I think that we'll see an economic depression where the demand for oil drops more quickly than the natural decline rate of our oil supplies and the price falls even further than it did in 2014-15. We won't be using nearly so much oil as at present, so we will once again accumulate a surplus, and we'll even leave some reserves of oil in the ground, at least initially. This will help drive a recovery after the depression bottoms out (point "e" in the diagram). Please note that I am talking about the remaining relatively high EROEI conventional oil here. Unconventional sources just don't produce enough surplus energy to fuel a recovery.

But the demand for oil will still be a lot less than it is today and this will have a very negative effect on oil companies. Some governments will subsidize the oil industry even more than they have traditionally, just to keep to it going in the face of low prices. Other governments will outright nationalize their oil industries to ensure oil keeps getting pumped out of the ground, even if it isn't very profitable to do so. Bankruptcy of critical industries in general is going to be a problem during and after the crash. More on that in my next post.

During the upcoming crash and depression fossil fuel use may well decline enough to significantly reduce our releases of CO2 into the atmosphere—not enough perhaps to stop climate change, but enough to slow it down. As we continue down the bumpy road, though, our use of fossil fuels and the release of CO2 from burning them will taper off to essentially nothing, allowing the ecosphere to finally begin a slow recovery from the abuses of the industrial age.

The other trend involving fossil fuels, as we go further down the bumpy road, will be their declining availability as we gradually use them up. Eventual our energy consumption will be determined by the local availability of renewable energy that can be accessed using a relatively low level of technology. Things like biomass (mainly firewood), falling water, wind, passive solar, maybe even tidal and wave energy. Since these sources vary in quantity from one locality to another, the level of energy use will vary as well. Where these sources are intermittent, the users will simply have adapt to that intermittency.

No doubt some of my readers will be wondering why I don't think high tech renewables like solar cells and large wind turbines will save the day. The list of reasons is a long one—difficulty raising capital in a contracting economy, low EROEI, intermittency of supply and the difficulty (once fossil fuels are gone) of building, operating, maintaining and replacing such equipment when is wears out—to mention just a few.

Large scale storage of power to deal with intermittency will in the long run prove infeasible. Certainly batteries aren't going to do it. There are a few locations where pumped storage of water can be set up at a relatively low cost, but not enough to make a big difference. And on top of all that, I very much doubt that large electrical grids are feasible in the long run (and I spent half my life maintaining on one such grid).

The FIRE Industries

The next trend I can see is in the FIRE (financial, insurance and real estate) sector of the economy. During the growth phase of our economy over that last couple of centuries the FIRE industries embodied a wide range of organizational technologies that facilitated business, trade and growth. Unfortunately, because they were set up to support growth, they were unable to cope with the end of real growth late in the twentieth century. They have supported debt based growth for the last couple of decades as the only alternative that they could deal with. This led to the unprecedented amount of debt that we see in the world today. Much of this debt is quite risky and will likely lead to a wave of bankruptcies and defaults—the very crash I've been talking about.

The FIRE industries will be at the heart of that crash and will suffer horribly. Many, perhaps the majority, of the companies in that sector won't survive. In today's world they wield a great deal of political power. During the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007-8 that power was enough to see them through largely unscathed. This is unlikely to be the case in the upcoming crash, creating a desperate need for their services and an opportunity to fill that need which will be another factor in the recovery after the crash bottoms out. But of course there is more than one way it can be done.

In the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th posts in my " Collapse Step by Step" series, I dealt with the political realities of our modern world, which limit what can be done by democratic governments. I identified a political spectrum defined by those limits. At the left end of this spectrum we have Social Democratic societies, which still practice capitalism, but where those in power are concerned with the welfare of everyone within the society. At the right end we have Right Wing Capitalist societies where the ruling elite is concerned only with accumulating more wealth and power for itself.

Since the FIRE industries are crucial to the accumulation and distribution of wealth in our societies, the way they are rebuilt following the crash will be largely determined by the political goals of those doing the rebuilding.

At the left end of the spectrum there is much can be done to regulate the FIRE industries and stop their excesses from leading immediately to further crises.

At the right end of the political spectrum the elite is so closely tied to the FIRE industries and so little concerned with the welfare of the general populace, that those industries will likely be rebuilt on a plan very similar to their current organization. A policy of "exterminism" is likely to be followed, where prosperity for the elite and an ever shrinking middle class is seen as the only goal and the poor are a burden to be abandoned or outright exterminated.(Thanks for Peter Frase, author of Four Futures—Life After Captialism for the term "exterminism".)

In the case of either of these extremes, or anywhere along the spectrum between them, there are some common things I can see happening.

The whole FIRE sector depends on trust. In the last few decades (since the 1970s) we have switched from currencies based on precious metals to "fiat money" which is based on nothing but trust in the governments issuing it. This was done to accommodate growth fueled by abundant surplus energy and then to facilitate issuing ever more debt as the surplus energy supply declined. I don't advocate going back to precious metals—what we need is a monetary system that can accommodate degrowth, of which a great deal lies in our future. Unfortunately we don't yet know what such a system might look like.

It is clear, though, that the coming crash is going to shake our trust in the FIRE industries to its very roots. Since central banks will have been central to the monetary problems leading to the crash, they may well be set up as scapegoats for that crash and their relative lack of success in coping with it. People will be very suspicious after watching the FIRE industries fall apart during the crash and their lack of trust will force those industries to take some different approaches.

I think governments will take over the functions of central banks and stop charging themselves interest on the money they print. Yes, I know that printing money has often led to runaway inflation, but the conditions during the crash and its aftermath will be so profoundly deflationary that inflation will not likely be a problem.

The creation of debt will be viewed much less favourably and credit will be much harder to get. And of course this will make the crash and following depression that much worse. In response to this many areas will create local banks and currencies to provide the services and credit that local businesses need to get moving again.

During the last couple of decades there has been a move to loosen regulations in the FIRE industries, to let single large entities become involved in investment banking, business and personal banking, insurance and real estate. Most such entities began as experts in one of those areas, but one has to question their expertise in the new areas they moved into. In any case they became "too big to fail" and their failure threatened the stability the whole FIRE sector. Following the GFC there was only minor tightening of regulations to discourage this sort of thing. After the upcoming crash I suspect many governments, especially toward the left end of the political spectrum, will institute a major re-regulation of the FIRE industries and a splitting up of the few "too big to fail" companies which didn't actually fail.

It is all very well to talk about business and even governments failing when their debt load becomes too great. But there is also a lot of personal debt that is, at this point, unlikely ever to get paid back. What does it mean, in this context, for a person to fail? What I carry as debt is an asset for someone else—probably the share holders of a bank. They are understandably reluctant to watch their assets evaporate, and I have to admit that there is a moral hazard involved in just letting people walk away from their debts. That feeling was so strong in the past that those who couldn't pay their debts ended up in debtors' prisons. Such punishment was eventually seen as futile and the practice was abandoned and personal bankruptcies were allowed.

One suspects that in the depression following the coming crash it will be necessary to declare a jubilee, forgiving large classes of personal debt. What might become of all the suddenly destitute people depends on where their country lies on the political spectrum. I wouldn't rule out debtors prisons or work camps, the sort of modern slavery that is already gaining a foothold in the prison system of the United States.

If we were willing to give up growth as the sole purpose of our economic system, there are many changes that could be made to the FIRE industries that would allow them to provide the services needed by businesses and individuals without stimulating the unchecked growth that leads to collapse. I think we are unlikely to see this happen after the upcoming crash—we will be desperate for recovery and that will still mean growth at destructive levels.

I think the crash following that recovery will involve the food supply and still unchecked population growth and sadly a lot of people won't make it through (more on this in my next post). Following that, it's even possible that in some areas people may reach the conclusion that growth is the problem and quit sticking their heads up to get slapped down again. They'll have to find a more sustainable way to live, but with it will come a less bumpy road forward.

Authoritarianism

In the aftermath of the next crash, I think we'll see an increase in authoritarianism in an attempt to optimize the systems that failed during the crash—to make them work again and work more effectively. Free market laissez faire economics will be seen to have failed by many people. Others will hang tight, claiming that if they just keep doing yet again the same thing that failed before, it will finally work.

As is always the case with this sort of optimization, it will create a less resilient system, much more susceptible to subsequent crashes. And after those crashes government will be reduced to such a small scale affair that authoritarianism won't be so much of an issue.

Fortunately, beyond authoritarianism, there are some other trends that will lead to increased resilience and sustainability. We'll take a look at those in my next post.

Links to the rest of this series of posts:

Political Realities / Collapse Step by Step / The Bumpy Road Down

- Collapse Step-by-Step, Part 1: Unevenly, Unsteadily and Unequally , Tuesday, 23 May 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 2: End Points, Friday, 16 June 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 3: Political Compasses , Saturday, 29 July 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 4: Political Positions, Sunday, 6 August 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 5: Political Realities, Wednesday, 30 August 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 6: More on Political Realities, Monday, 9 October 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 7: More on Political Realities, Continued, Friday, 13 October 2017

- Collapse Step by Step, Part 8--The Bumpy Road Down, Part 1, Sunday, 26 November 2017

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 2, Sunday, 7 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 3, Monday, 15 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 4: Trends in Collapse, Friday, 26 January 2018

- The Bumpy Road Down, Part 5: More Trends in Collapse, Tuesday, 20 February 2018

20 comments:

Nice essay Irv.

I observe that you do not predict adults discussing the implications of declining net per capita energy and rationally choosing an optimal system for their predicament. It's tragic that evolved behavior prevents us from using our intelligence in a constructive manner when it really matters.

Nice to hear from you Rob!

I guess I'd say that I don't think there are absolutely no adults who could do this. Just relatively few. Few enough that it won't make much difference. Whether that is because of evolution or the nature of the current situation is hard to tell, and doesn't matter that much because the result it the same.

A more important question is, can those few who are capable of doing something constructive really make any difference, even for themselves and their families and communities? If it is possible, it won't be easy.

Thanks for the insightful article. You have a good combination of current facts and predictions, all of which make sense.

Not a pretty picture, Irv, but I think you've done your homework well. Looking forward to the next in the series.

@Jude Lieber

Thanks! And I try not to make precise predictions about dates or exact events. It's a fools game.

But I hope a clearer grasp of the trends that are at work will be of help to people.

@foodnstuff

Hi Bev! It's nice to hear from someone else who is aware of collapse and can still see that I'm not looking through rose coloured glasses.

Thank you for these insightful and balanced posts. Since I discovered your blog a month ago or so, I've been eagerly checking back here daily for new articles.

Just curious to know if you're familiar with the works of Michael Parenti? Some of it is collapse-related. I'm reading Against Empire: A Brilliant Expose of the Brutal Realities of U.S. Global Domination. It was published in the mid 90's and is perhaps somewhat dated, but I doubt things have actually changed much since then. I find it illuminating.

Another clear and perceptive post. Well done.

I still think that the most complex industrialized societies will have a tough time arresting any precipitous decline in carrying capacity, but even if I am wrong about that, the most prudent course of action would be to prepare for rapid descent to subsistence agriculture.

Even if the decline is as bumpy as you describe, the drops in resource availability will mean lots of premature death (even without any consideration of war and pandemic). If an economy shrinks by half, half of its workers will lose their jobs. Jobs are how we now distribute essential resources. Those who become jobless and still depend on society to provide food, water and shelter will be taking a great risk and great leap of faith. True prudence requires being able to live without money. It's hard to do in a developed country, but that should still be the goal.

I suspect that the complexity of high-energy, high-tech societies will mean that they are at even greater risk than poor and predominantly rural developing countries. Developed countries are like finely tuned machines. There are some repair services available, but I wonder how many parts they can lose before the machine stops working completely?

I used to work in a combined-cycle power plant. Without the integrated circuits in the SCADA system, the plant would need dozens of operators to keep it going, if it could be done at all. To paraphrase an old saying, "For the lack of a chip, the powerplant is lost; for the lack of a powerplant, the grid is lost; for the lack of the grid, civilization is lost." Perhaps one of your next installments will explain how civilization could adjust to an absence of microprocessors.

Irv,

I just found your blogs yesterday, beginning with The Biggest Lie.

As an evolutionary biologist (PhD Harvard, 1973) and a documentation and knowledge management systems analyst and designer (17+ years with Australia's largest defence contractor and shipbuilder until my 'retirement' in 2007), I too am concerned about the impending collapse of the human species.

For more than 10 years I have been working to understand the coevolution of humans and our technologies tracing from our common ancestry with chimpanzees and bonobos. See Application Holy Wars or a New Reformation - A Fugue on the Theory of Knowledge for a detailed overview of the project. My initial conclusion was that a technological collapse/singularity as a consequence of hyper exponential growth in the technology and associated environmental destruction was inevitable.

More recently, as I began to consider environmental impacts, it seems more likely that collapse will be the result of runaway global warming rather than any specific consequence of technology. See The Angst of Anthropogenic Global Warming: Our Species' Existential Risk and Is this the start of runaway global warming?. I have also established a Facebook presence to discuss such things. See Facebook.

In this regard, your analyses of existential risk and the mechanics of collapse are among the best I have read anywhere - and certainly a lot clearer than my attempts. Would you object if I added links to your discussions in my posts and documents? I would also be happy to correspond offline on william-hall@bigpond.com.

Nice series Irv, thank you. I just ran across your blog while visiting ROE2, and have been catching up with your writings. I am in general agreement.

One of the puzzling reason we seem to be headed down this path, would appear to be that it is "hard wired" into life on this planet. Whether you are looking at yeast on a petri dish, rabbits and foxes, or humans and resources, all seem to rush forward full speed ahead, with little thought (or feedback) about the longer term consequences.

If you could go down to that petri dish and "chat" with the microbes growing there, and explain how they double every 90 mins and they've half consumed their world already, they need to think about multiplying so fast; do you think they would listen and change their behavior? Likely they'd tell you to "buzz off, things have never been better and look there's lots of agar left". This was the story line behind the various "Are humans smarter than yeast" threads some years ago.

I suspect the conversation would go much the same way with the rabbits and foxes too. There do not seem to be too many (any?) "success stories" out there where the "hero" was a critter that shunned the grab as much as you can as fast as you can

ethic and prevailed.

Having been involved in the peak oil movement for many years, I can say that the conversation certainly does go much this same way with humans too. And while we humans have numerous positive feedback loops (such as our political/economic system) which tends to reinforce the path we are on, in the long run I don't know that is really any different than the biochemical urges the yeast cells feel and act on.

That and I see little evidence that people are willing to give up convenience until they absolutely have to. A few do, but not enough to make a significant difference in the outcome (at least not yet).

So until this pattern changes, I expect we will follow the curves you've outlined, and reality will take away those conveniences we just "have to have".

The energy return of wind and solar energy is certainly nowhere near as high as historical oil gushers, but it is definitely better than current marginal petroleum, ie. fracking. Solar is not as good as wind, but it is catching up, and wind itself is still improving. Petroleum may be a crucial resource for select purposes, but it's not unusual to leverage energy from an inexpensive source into extraction of a more useful resource with a lower or even negative net energy return. Leveraging inexpensive intermittent stationary energy sources into valuable storeable, transportable, dispatchable fuel makes great economic sense, even if the production of the fuel has negative energy return — it’s just bad for the climate if the fuel in question is a fossil fuel.

All sophisticated economies are debt-based. Circulating currency is a debt obligation of the issuing government. Post-war prosperity of Western nations has been underpinned by ongoing deficit spending by governments, ie. ever-increasing debt. This is entirely sustainable. Any large or sustained surplus sucks money from circulation and triggers recession. It is a fiction that currency-issuing governments borrow money from the private sector: they do sell bonds to the private sector, but central banks “make the market”, always willing to buy or sell at the chosen price (thereby fixing bond yield and interest according to policy). Any bonds held by the central bank are “intra-governmental” debt and (just like circulating banknotes) incur no interest burden. Public debt is a monetary tool for controlling the financial conditions in which the private sector operates, not a means of funding the government.

Real economic growth in a global sense hasn’t stopped since the 1970s or even since the 1990s: it has just largely left the working classes of the developed countries behind. Workers in most developing countries have become vastly better paid in that period. Even in developed countries there is still ongoing economic growth, it has just been concentrated mainly in the hands of capitalists rather than steadily increasing wages at the low end.

National currencies have always been “fiat” and were never really “based on” precious metals. The exchange value of fiat currencies does not depend on *trust* in the governments which issue them, but on the productive capacity of the economies using them, and the power of the issuing governments to levy taxes in their own currency.

The real purchasing power of a currency has always been determined through public policy, ie. spending and taxation. Whenever a nation’s supply of precious metal fell behind its spending needs, it would suspend convertibility. For example, Britain unofficially adopted a gold standard in the final years of the 17th century but would repeatedly abandon it when military spending outstripped gold supplies, reimposing it after the peace, forcing deflation and triggering painful recession. Recoveries in the imperial era were driven by centripetal accumulation of wealth from the colonies. What we think of as the “roaring twenties” was roaring enough in the USA and international financial centre London, but most of the UK struggled from the postwar reimposition of the gold standard in 1925 until convertibility was suspended once and for all in 1931. Arguably the British depression from 1925 was the trigger for the flight of capital to New York, the late 20s stock market boom and crash, and the wider Depression of 1929-1938.

The final international abandonment of the gold standard really occurred in the 1930s Depression, not in the 1970s. Bretton Woods created an ersatz gold standard based on the US Dollar, with the US Government undertaking to exchange its dollar for a fixed quantity of gold, to foreign buyers only. Ultimately that guarantee had to be repudiated, and the inflation inevitable from decades of deficit spending finally unravelled into consumer prices as currencies were allowed to float.

What changed, not really abruptly in the 1990s but gradually starting in the 1970s, has been the movement by developed country governments and central banks to prioritise low inflation over full employment. This was hardly necessary, as the two major causes of 1970s “stagflation” were strictly temporary: the unravelling of the false Bretton Woods gold standard and the co-ordinated OPEC oil price hikes from 1973 to 1981. The tool of choice for unnecessarily combatting inflation has been monetary policy, ie. high interest rates, which reduced private-sector investment and employment, and also cuts to public sector full employment strategies. Any residual post-stagflation inflation has indeed been defeated in the developed economies, as intended, through reduced domestic investment and employment.

@Ben

Thanks for your kind words. I hadn't heard of Michael Parenti. I've put Against Empire on my Amazon wish list and look forward to reading it. Not many are willing to call the USA an empire, but I find it a very useful viewpoint.

@ Joe

I completely agree: regardless of the exact path that collapse takes, it would be extremely prudent to prepare for a quick descent to subsistence agriculture, and to situate ones self in an area where that is feasible. I wrote a series of posts on this a few years ago, entitle "Deliberate Descent", http://theeasiestpersontofool.blogspot.ca/2013/08/deliberate-descent-part-1.html. I currently live in a small town on Lake Huron, in the middle of an agricultural area. I am the co-orinator for the town's Community Garden and I'm working hard at learning to garden effectively.

During a crash developing countries will find themselves out from under the imperialist yoke, and for those outside the large cities life may go on much as it has for centuries, provided climate change doesn't make low tech agriculture impossible.

Before I retired, I worked in the transmission and distribution section of Ontario's power system, for the most part in the switchyards associated with a large nuclear generating plant. We were becoming more reliant on solid state electronics all the time. Because that is a new technology, all development efforts have tended to focus on taking it to the next level, rather than applying it at an "appropriate level". But if that focus was to change, it wouldn't take long to set up small scale chip foundries close to wherever those parts are needed. Failing that, it wasn't very long ago that the whole power system was run with nothing more high tech than electromechanical relays and the odd vacuum tube--it just takes a lot more people. People, as you point out, are one resource we will have in abundance. To borrow John Michael Greer's terminology, we will need to engage in some "rehumanization".

@anonymus, William Hall

I was a pleasure to hear from you and rather flattering. I had a quick look through the links you included and I see nothing that I wouldn't want my name associated with. So, yes, please feel free to go ahead and link to my blog.

@Steve

I've been a member of the ROE2 list since 2006 and I've been sending notices about my blog posts to the list for some time now. It's nice to see that they haven't been completely ignored. I'm glad you like what I'm doing here--on the fine points, of course, there is room for many and varied opinions.

Human beings are extremely adaptable, but we don't go making big changes in our way of life until need becomes extremely clear. That's probably a good thing in most circumstances, but in our present situation it means we'll wait until the only way left to adapt is the hard way. And sadly, it means that most people aren't going to make it through the bottleneck that lies ahead.

I just hope that I can help some of my readers be a little better prepared for what's coming.

@ Jonathan Maddox

I have a feeling what you're really trying to tell me is that everything is going to be OK. Pretty clearly I don't agree with that. I could turn the details of that disagreement the subject of a lengthy series of posts (and maybe I will) but I don't feel that here in the comments is the most productive place to get into it at length. I've done this in the past, and looking back, it was a mistake.

Just a few points in response, though:

1) there simply isn't any viable alternative to oil (or coal or natural gas) in many of the industrial processes on which our civilization is based. If we just needed a bit of oil, then spending some of the available energy from renewables to get that oil would make sense. But in the quantities we need to "sustain business as usual", it's simply not practical.

2) As I've said, I've nothing against debt based currencies as long as the economy is growing, but when growth slows, it become less and less likely that the debts can be repaid, until finally the whole house of cards falls down. And growth has slowed, if not quite yet stopped. I gather you disagree, but I'm not so easily dissuaded. My preferred source on this is Tim Morgan, of Surplus Energy Economics, https://surplusenergyeconomics.wordpress.com/

A good summary of his ideas can be found in his essay "perfect storm", https://www.tullettprebon.com/documents/strategyinsights/TPSI_009_perfect_Storm_009.pdf

or in his book, "Life After Growth".

Hello Irv, thanks for your reply.

I certainly wasn't attempting to say that "business as usual" would proceed unhindered. There are numerous other constraints to rapacious capitalism and never-ending material consumption besides energy, and a wholesale energy transition itself is not without significant economic costs. I subscribe to the "bumpy road down" theory right along with you ... we are definitely in for a lot of painful bumps, and we will certainly not come out the other end with comparable consumption (magnitudes or habits) as are "enjoyed" today. On the other hand, we won't be bumped all the way down to subsistence agriculture: our technical knowledge and much of our existing infrastructure will remain available for use through any economic disruption.

Energy itself is readily available in vast quantities. Not only is the potential supply from the sun (via wind or solar technologies) a couple of orders of magnitude greater than the current rate of fossil fuel extraction, with comparable net energy return to average fossil fuel extraction (today, not historically) but It must be recognised that not all energy resources are of equal cost or of equal utility, and that humans, especially desperate humans, will readily spend lots of a cheap abundant resource to obtain a small amount of a prized scarce one. People incorrectly infer an imminent "energy cliff" from the declining net energy return of petroleum, but so long as abundant and inexpensive energy is available in another form (renewables, coal, nuclear, whatever) which can either be used to manufacture liquid fuel without petroleum, or be leveraged to continue petroleum extraction despite low, zero or negative net energy, no such energy cliff exists. The gross magnitude of the petroleum resource, if net energy concerns are set aside, is staggering, so "there's enough to fry us all". We need to restrict fossil fuel burning through political means because of pollution. Energy scarcity will not do the job for us by itself, because energy just isn't scarce.

Despite denialism and heel-dragging in many powerful circles, there most certainly is a political and technocratic movement to restrict the use of fossil fuels and to reduce our technical reliance on them, and it is seeing some success. Coal is the low hanging fruit; global coal consumption has declined for two years in succession. Oil and gas have scarcely been targeted yet, and while there are fewer obvious replacements (especially once we necessarily come to disallow substitution of one fossil fuel for another), they will be targeted and technically can be replaced in their largest applications.

While it's true that for many present-day industrial processes familiar liquid, gaseous or solid fuels are necessary, it is not true that the only possible sources of liquid, gas and solid fuels are fossil fuels, nor is it especially important for the survival of civilisation (survival, not BAU) that we continue to use those processes as inefficiently as we do today, nor at the same enormous rates as today. There *will* be de-growth in material consumption volumes. Substitution of non-fossil energy for fossil fuels is already widely demonstrated in the processes which use the lion's share of fossil fuels today, namely electricity generation, personal surface transportation, process heat, space heating and nitrogen fertiliser manufacture. Even if we *only* swapped out fossil fuels in those applications, while continuing to use fossil fuels in the same manner as today for aviation, heavy surface freight, metallurgy and other chemical processing, we would indeed find that we "just needed a bit of oil", relative to today's consumption anyway. Those applications represent, very roughly, just 20% of present gross fossil fuel consumption. On our "bumpy road down" not only will gross throughput fall, it's also likely that consumption efficiency will improve at every opportunity.

In the longer term, there really are non-fossil substitutes for every fossil energy resource: the existence proofs are synthetic hydrocarbon fuels (can be made using water, carbon dioxide and electric energy) and metallurgical charcoal as used on an industrial scale today in Brazil (dirty and destructive without a doubt, but definitely not fossil fuel).

@ Jonathan Maddox

I am going to bring this discussion to a close here, sincer I can tell there is nothing to be gained for either of us.

It's nice that you agree with my bumpy road down idea and I'll admit that I suspect some areas, especially those with abundant hydro power, may well end up retaining a relatively high level of technology. Note I say "relatively".

To make it clear where I am coming from to those who are reading along:

Your "vast quantities" of energy are nothing more than a mirage. Surplus energy concerns apply not just to fossil fuels, but to all sources of energy. And it's the overall average EROEI of a country or planet that counts, and goes to determine the level of growth it can sustain. A good rough figure is 15 to support the kind of civilization we are accustomed to. Today's world average is 11 and falling. Already too low to sustain a high tech civilization.

Post a Comment