|

| We've had a lot of snow recently in Kincardine |

In this series of posts I've been talking about why I think our industrial civilization has been slowly collapsing since the 1970s, and is likely to continue to do so until circumstances have forced us to adopt a sustainable lifestyle. In the light of the issues I'll be talking about in this post, I should make it clear that I don't think of collapse as a problem to be solved, but rather as a predicament to which we must adapt. And there is a lot of room for different opinions as to what exactly those adaptations should be.

My last few posts have sparked some discussion on a couple of issues that I think are worth devoting the entirety of this post to, before I go on with scheduled programming, so to speak.

Footprints

The first is what "footprint" actually means. The best source I can recommend for this is the Global Footprint Network and their Ecological Footprint measure. I found their FAQ page answered most of my questions. Interestingly, the most surprising things I found out are about what the Ecological Footprint isn't. Which lead me to the Water Footprint Network and the concept of Carbon Footprints. For the issues of dwindling non-renewables like fossil fuels and minerals it was harder to find anything like "footprints", but Wikipedia does have an article on resource depletion which may serve as a good jumping off point if you want to do further reading.

What footprint definitely does not mean is "square miles per person". This is clearly a confused approach to the subject, since hunter-gatherers who have a very low impact on the ecosystem use a lot of square miles per person, but step very lightly wherever they go. While modern humans occupy a relatively small area of land each, but have a very heavy impact on the planet.

The Ecological Footprint uses a measure of "global hectares per person" where "one global hectare is the world's annual amount of biological production for human use and human waste assimilation, per hectare of biologically productive land and fisheries."

"In 2012 there were approximately 12.2 billion global hectares of production and waste assimilation, averaging 1.7 global hectares per person. Consumption totaled 20.1 billion global hectares or 2.8 global hectares per person, meaning about 65% more was consumed than produced. This is possible because there are natural reserves all around the globe that function as backup food, material and energy supplies, although only for a relatively short period of time."

Those quotes are from Wikipedia's short article on "global hectares", which may serve to clarify what I am talking about here.

Overpopulation or Overconsumption?

The second issue was a disagreement about whether overpopulation or overconsumption is the main problem contributing to the overshoot situation we are facing. Opinions on this seem to lie on a spectrum, interestingly coinciding somewhat with the left to right political spectrum. In my discussion of this below, I'll be disregarding the people who don't think there is a problem to worry about at all, who don't believe that we are or ever will be in overshoot. They are either in denial or have immense and unjustified faith in progress and technology. But that is a whole different story.

First I should note that the problem is not just that there are too many people or that they are consuming too much, but also that both our population and our consumption are growing. Even if we didn't have a problem yet, growth means that we soon would have. Of course, we clearly do have a problem and have had since the 1980s when our impact went above the carrying capacity of the planet. Growth just means it's getting continual worse.

My friends on the left aren't terribly concerned about overpopulation. What they are concerned about is excessive consumption by the upper class. If that can be eliminated, and the lot of the poor improved accordingly, they believe that the demographic transition will continue and population will peak out at a level that the planet can support. They also speak about reducing waste in the food production system, which would be a good idea. And they have quite a bit of faith that technology will assist with all of this. If you suggest that we should be actively trying to reduce our population, they may well label you as an "eco-fascist".

Which brings us to the other end of the spectrum, where there actually are some eco-fascists. But most of the people I know who are saying that overpopulation is the source of our problems also acknowledge that over-consumption is a big concern. They mention overpopulation first because they are concerned that it doesn't get enough attention.

There are some people, though, who focus entirely on overpopulation and believe the overconsumption is solely the result of overpopulation. Worse yet, they take the fact that an abundance of food facilitates population growth and then jump to the conclusion that having less food available is the only effective way to get our population to decrease. The problem with that idea is that it doesn't fit the facts.

First, these folks will tell you that we are continually increasing the food supply and because of this the population is growing at a steady 1.4% per year. In fact, while the level of food production has been increasing, the population growth rate peaked in the 1960s at around 2% and has been decreasing since then, to around 1.05% in 2020.

In the developed nations the population growth rate has decreased to below the replacement level in many cases. And that is with an excess of food.

In the developing world, fertility and the population growth rate are still high. This despite the fact that many people are suffering from malnutrition—around eight hundred million globally, most of them in the developing world.

The eco-fascists say that if the food supply was gradually decreased, gradually increasing malnutrition would cause a reduction in fertility and with it falling population growth rates, and without causing undue hardship. But while severe malnutrition does reduce fertility, the response of fertility to minor levels of malnutrition is much more complex.

As for avoiding hardship, in the real world of markets where we ration by price, if there is a shortage of food then the price of food goes up, and the poorest people in the affected area experience what amounts to famine driven by economics. In many cultures this is more likely to spark a revolution than to decrease fertility, as it did in several countries when food prices spiked at the start of what has been called the "Arab Spring". This was less a matter of a sudden desire for democracy than a reaction to an increase in the price of food.

The negative effects of a plan to control population growth rate by reducing the food supply would fall disproportionally on poor, brown people, and this is where the term "eco-fascist" arises. Labels aside, oppressing the poor and weak seems to me like a pretty despicable thing to do. Especially since it would not, as we'll see in a moment, achieve the desired result of reducing our degree of overshoot.

Even though my politics are pretty far left, my ideas on overpopulation versus overconsumption lay somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. I've been looking at humanity's impact on the planet using the I=PAT approach, which considers the effects of population, affluence (consumption) and technology. It's pretty clear that our impact is already greater than the carrying capacity of the planet (about 165%), with both population and consumption contributing to this, and both continuing to grow. It is clear that the per capita level of consumption is increasing, so that something beyond just population growth is driving growth of consumption. You mighty characterize this as "increasing affluence", which gives the problem a name, but doesn't do much to solve it.

It is also important to keep in mind that where ever our impact is greater than the carrying capacity, the ecosystem is being damaged, and carrying capacity decreases. This makes our situation even worse.

Much of our current consumption relies on non-renewable resources. As these resources become depleted, it costs more and requires more energy to access them. This takes us further into overshoot in a way that I don't think is adequately represented by footprint or impact measures. The depletion of resources we rely on, and don't have adequate substitutes for, is a major driver of collapse.

For a long lived species such as ours, there is a lengthy delay between reducing the rate at which our population grows, and actually reducing the population. At best, if the demographic transition keeps spreading in the developing world, and the population growth rate continues to decrease, it will be many decades before our population stops growing. During that time our impact will almost certainly exceed the carrying capacity of the planet by a much greater extent than it does at present. I would expect this will result in a significant dieoff of the human population.

So, I believe we should still do everything we can to reduce population growth, including educating women, striving to give them more control over their lives, and making birth control more readily available. We should not do anything that would be morally abhorrent, lest the solution be worse than the problem.

We also need to look elsewhere for something that can be done to reduce our impact in the short run, before overshoot catches up with us.

In the decades since Paul Erlich proposed the I=PAT approach, many have turned to technology as the most promising way to reduce our impact. It is the only approach that doesn't call for significant changes in lifestyle, especially for rich people. Sadly, no real technological solutions have been forth coming. The oft promised "decoupling" hasn't happened, and there is good reason to think that it won't ever. Many new technologies actually consume more, especially more energy—take bit coin, for example. I'll go into that in more detail in an upcoming post.

The only remaining alternative to reduce our impact would be to reduce consumption. This is something most people are unwilling to do, but I believe we that must, and that we can. While overpopulation will take a long time to address, overconsumption can be reduced almost immediately, as we have seen during the current pandemic.

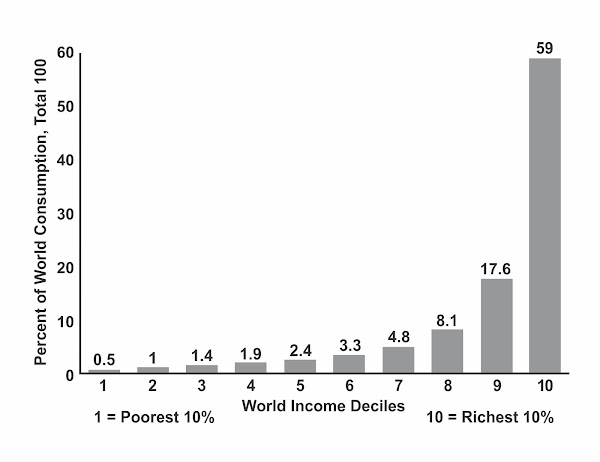

Consider the graph below, which charts world income deciles against consumption.

Figure 1

I guess it's no surprise that richer people consume more, but how much more is pretty shocking.

Based on this graph, 59% of consumption is done by the top 10% of the richest people in the world. The bottom 50% of the people, the poorest people in the world, do only 7.2% of the consumption. If we were to get rid of the bottom 50% of our population, it would have very little effect, leaving our impact at 153% of carrying capacity( .928 times 1.65 = 1.53). On the other hand, if we were to get rid of the richest 10%, it would reduce our impact to 68% of carrying capacity(.41 times 1.65 = .68). Of course, I am not proposing that we set out to "get rid" of anybody, but this does show why I think that we should be looking at reducing consumption as well as population. And why I think people who want to stop poor folks from breeding are barking up the wrong tree.

Before we can take a close look at what drives consumption, and the growth of consumption, I think we need to look at several touchy subjects—human nature, our needs and wants, and politics. I'll do that in my next post.

Here is some additional reading on the subject of population growth and malnutrition: https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/4523

Links to the rest of this series of posts, Collapse, you say?

- Collapse You Say? Part 1, Introduction, Tuesday, 30 June 2020

- Collapse, you say? Part 2: Inputs and Outputs, Wednesday, 30 September 2020

- Collapse, you say? Part 3: Inputs and Outputs continued, October 7, 2020

- Collapse, you say? Part 4: growth, overshoot and dieoff, January 2, 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 5: Over Population, January 8, 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 6: Over Population and Overconsumption, Februrary 21, 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 7: Needs and Wants, Human Nature, Politics, March 8, 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 8: Factors which made industrialization possible, May 13 , 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 9: Unintended Consequences of Industrialization, May 20 , 2021

- Collapse You Say? Part 10 / Time for Change, Part 1: Money, January 5, 2022

- Time for Change, Part 2: Hierarchies, Februray 16, 2022

- Time for Change, Part 3: Without Hierarchies? April 23, 2022

- Time for Change, Part 4: Conclusions June 22, 2022

24 comments:

Irv, I have been thinking about that I-PAT function and think there should be a fourth term on the right, E for entitlement.

The problem with the graph of consumption is that there is an equivalent increase in E as wealth increases. That makes it an emotional and political problem, as you mentioned in the text. The rich, and that includes most of us feel entitled to our unfair share. If we look for it, we discover that proportionately more poor people think about sharing than the rich, and they especially don't demand accolades and a photo-op when they do.

To have a rational solution to our destroying life on the planet, we need to negate rich-world entitlement. As you know from our discussions, I think we are doomed to awaiting nature to do it to us. As our recent, on going example, Texas demonstrates natural impacts are the most democratic processes in the world. Covid19 also fits but in current circumstances, the entitled few are still faring better and we will until we too can not. As you know, I remain pessimistic on us avoiding the natural form of democracy.

@ Don Hayward

I agree completely--entitlement among those who are overconsuming is going to make it hard to fix this problem or even to get people to adapt to consuming less. I meet people fairly often who say they would rather die than change their lifestyle.

I have little doubt that mother nature will have to take the matter in hand. Indeed she has already begun to do so. In the coming decades we will be forced to get by with less, because that is all that will be left for us. I only hope to make a few more people aware of what is ahead, and to suggest what sort of adaptations and preparations might be most helpful. There are no guarantees in any of this, but those who are aware and even somewhat prepared will have a better chance than those who aren't. Still not a great chance, but better.

@ Don Hayward

One further thought--if you live an affluent lifestyle for any significant amount of time, it highly likely that you end up feeling entitled to it.

Entitlement by the rich is an obvious problem. How to stop it is an extremely difficult question. I still don't support "Eat the Rich" though - even as a joke. I would support taxing the heck out of them and sharing the money. Remembering a scene from Dr. Zhivago, when he comes to his house and finds dozens of people there. He says "Yes, comrades. This is more just." And he and his family still have their own room.

Irv, the word collapse is maybe inaccurate to describe the over consumption issue. It could be collapse or it could simply a slow change.

Over consumption can be easily solved in my opinion with lifestyle changes, starting with the food we eat. The consumption footprint of Vegans is amazingly small compared to other food consumption. Soil erosion, deforestation, water pollution, water consumption, species extinction, green house gases, climate change, to name a few problems of meat consumption

One pound of beef needs ten pounds of grain. The rest is polluted byproduct. This does not even address the health cost of non vegans. Heart surgery is a multi billion dollar industry in the US, so is type 2 diabetes, also the number one factor for cancer is over weight (meat eaters).

It is pretty hard to do. But can be done. Everyone is in denial about this solution. It has to be solved through taxation of the affluent consumers. We tax gasoline consumption and accept it as an example.

The Ecological Footprint uses a measure of "global hectares per person" where "one global hectare is the world's annual amount of biological production for human use and human waste assimilation, per hectare of biologically productive land and fisheries."

This definition can easily be converted to other units of area, including square miles, as in:

The Ecological Footprint uses a measure of "global 0.00386102 square miles per person" where "one global 0.00386102 square mile is the world's annual amount of biological production for human use and human waste assimilation, per 0.00386102 square mile of biologically productive land and fisheries."

I agree that the human footprint is not the same as population density. A densely populated area could have a lower total footprint than a sparsely populated area if the people in sparsely populated area consume far more resources or generate far more waste per capita.

However, when you say that "what footprint definitely does not mean is 'square miles per person'", you are conflating the concept of population density with the concept of Ecological Footprint. Ecological Footprint is indeed square miles per person of the earth's surface needed to supply enough resources and absorb enough waste for that person to live. People who use a lot of resources or generate a lot of waste have a large Footprint area no matter how close or far from each other they live.

I'll leave the issue of the per capita footprint of hunter-gatherers alone, except to point out that efficiency with which biological resources are used can affect the per capita ecological footprint. That efficiency is contained in the T term of I=PAT. If your wood stove needs only half as much wood as another's, you need to chop down only half as much wood and therefore have a lower ecological footprint. If, without importing any nutrients, you can grow more rice in your paddy than your neighbor, your ecological footprint is also lower than your neighbor.

Yes, I agree with Joe. You've stated that "what footprint definitely does not mean is 'square miles per person'" and then go on to give the definition, the Ecological Footprint uses a measure of "global hectares per person", which is just the same thing with different units. Change 'square miles per person' to 'people per square mile' which is population density and that is the difference you actually mean.

The thing I always take issue with in 'footprint' analyses is that it's never stated what the condition of the earth is in at the time of the measurement, and what is the ideal condition it should be in (which no doubt depends on opinion). In my view the ideal condition of Earth is one in which all species are living as sustainably as climate conditions allow and ecosystems are not being damaged by the activities of any one species to the detriment of other species. For me that means a time when all species are living as hunter-gatherers, including humans. Once humans started agriculture they began to take up more resources for their own use and that left less for other species, mainly by damaging and removing their habitats. That's my definition of the beginning of overshoot. It's just that it's taken thousands of years for the damage to become apparent to the point that it's now damaging human activities. So when we're told we went into overshoot sometime in the 80's (or whenever) that's only when we started noticing the effect on US. Other species had been in 'undershoot' for millennia and the planet's carrying capacity for them had been destroyed or lessened.

There are assumptions by all comments here as well as in the post that humans have free will in general. That is based upon a misunderstanding that we different than the rest of life. See:

https://www.ecologycenter.us/ecosystem-theory/the-maximum-power-principle.html

The bulk of humanity is doing all possible to increase energy throughput. That is what nourishes life and replication. It is automatic. The two rare exceptions I've thought of are suicide and voluntary simplicity. For the latter to be an option, one must have excess matter-energy available. There are billions which don't have that option.

Sperm counts are dropping due to pollution in water, soil, food chain. Births are declining due to air pollution as well. These are involuntary drivers. Women's empowerment certainly helps a lot, but fundamentalist religions (monotheistic: Muslim, Christian, Orthodox Judaism) encourage competitive breeding and then cultivate it in their progeny. They are old school patriarchal, and are growing far faster than the global average. Looks like negative feedback will be with us as population peak and declines this century.

@ Shodo

I too would support taxing the rich and heavily. While this would no doubt be more just, I am not sure it would solve the problem of excess consumption, just change who is doing it.

In any case, the rich are running things and the great majority of them feel completely entitled to their position, so it's unlikely that they would suddenly decide to start raising their own taxes.

I see three possible futures, in decreasing order of likelihood:

1) We try very hard to keep "business as usual" going for as long as possible. The rich get richer, the rest of us get poorer, and finally the ecosphere collapses from the strain.

2) Somewhere along the path outlined in scenario 1 "the rest of us" get fed up and stage revolutions, which are better than ecosystem collapse, but still pretty bad.

3) A majority of people smarten up, and we organize a "deliberate descent" or what some are calling degrowth, and both our population and consumption are deliberately reduced to a sustainable level, well below the carrying capacity, and the ecosystem is allow to recover.

Scenario 3 is is extremely improbable and, sadly, it is the only one where a majority of people end up understanding the problem and don't go back their previous bad habits after the dust settles.

@ Dave

I am simply not convinced that everyone becoming vegans is at all likely to happen, or if it did happen, that it would be the cure all that you paint it as. It seems to me like just another attempt to keep business as usual going along as usual, minus the food animals.

Further, I am not the least bit interested in any more discussion of the subject.

@ Dave

If you are new here, you may not realize that I conceive of collapse as a slow process, proceeding unevenly geographically, unsteadily chronologically, and unequally socially. While it may occasionally take fairly abrupt steps downwards, for the most part it proceeds quite slowly. So much so that most people have no more than a vague sense that things seem to be getting worse. And if you live in an area that is not hard hit and make enough money so that you are fairly isolated from reality, you would probably swear that the idea of collapse is nonsense and claim progress is continuing just fine.

The idea of "fast collapse" is a great plot devise for post apocalyptic fiction, but doesn't apply very well to reality.

@ Joe Clarkson

Initially I was puzzled by your response and couldn't figure out where you were coming from. Then the little light came on, and I realized you're thinking that "global hectares" is a unit of land area. While a hectare is a unit of area, and yes, any other unit of area would do as well, the term "global hectare" as it is used by the people at the Global Footprint Network, is definitely not a unit of area, confusing as that may seem. So, I am NOT "conflating the concept of population density with the concept of Ecological Footprint". At least if we both mean the same thing by "conflate", which my dictionary defines as "To fail to properly distinguish or keep separate (things); to mistakenly treat (them) as equivalent."

So what do they mean by "global hectares"? Well, they use it in two ways, first as a unit of biocapacity (biological production for human use and human waste assimilation), and second as a unit of consumption (known as the Ecological Footprint).

Every year they collect a whole bunch of statistics about the biosphere and use these to calculate what the capacity of the biosphere was that year. That is, the maximum it could have produced without sustaining any damage, which in many cases these days will be less than the it actually produced. This takes into account the efficiency with which resources were being used in an particular year, since it is looking back on what actually happened, rather than making any sort of prediction.

Then they look at the amount of biologically productive land and water area. The land and water (both marine and inland waters) area that supports significant photosynthetic activity and the accumulation of biomass used by humans. Non-productive areas as well as marginal areas with patchy vegetation are not included. Biomass that is not of use to humans is also not included. The total biologically productive area on land and water in 2012 was approximately 12 billion hectares. Divided by the human population, this gave 1.7 global hectare per person for 2012. Because world productivity varies slightly from year to year, the amount of biocapacity represented by a global hectare may change slightly from year to year.

Dividing the total productivity by the biologically productive land area gives you the global hectare, basically average productivity per average hectare. This is a pretty counterintuitive thing, since it is a unit of biocapacity, not a measure of land area, or a measure of population density. But it simplifies things because biocapacity is made up of many things, not just apples and oranges, but also so pomegranates and prunes, and many other various and assorted things. Global hectares represents them all in a single unit.

To calculate the Ecological Footprint, they look at what we actually did use in that particular year and looking at the productivity statistics, they determine how many hectares it would have taken to support us sustainably. In 2012, consumption totaled 20.1 billion global hectares or 2.8 global hectares per person, meaning about 65% more was consumed than produced.

The Global Footprint Network gathers statistics on a country by country basis. Here is a map they produce, showing the ecological deficit/reserve on all the countries in the world.

ecological deficit/reserve by country

Here is a page with definitions of various terms:

Definitions

I should make it clear that I am just trying to clarify how the Ecological Footprint works. It is the creation of the Global Footprint Network and I am in no way affiliated with them. In fact, looking closely at how the footprint is calculated, I can see some areas where it might be criticized.

@ Bev Courtney

Have a look at my reply to Joe Clarkson's comment. it's pretty confusing, but a Global Hectare is not a unit of land area, rather it is a unit of biocapacity or consumption, depending on how it is used. It is not population density, and that wasn't what I meant.

Because the footprint calculated by the Global Footprint Network is based on data collected from previous years, and applies only to those years (it's not a prediction) then it definitely does take into account the condition of the planet at the time, and adjustments are made to adjust for "ideal conditions" as you put it.

I grew up on a farm and I've done quite a bit of gardening since I left home. You may be right, but I think that we can do a certain amount of agriculture without being in overshoot. But not with 8 billion people living the kind of lifestyles we do today. Let's be honest with each other--collapse is going to continue and at some point there is going to be a fairly serious dieoff of the human population. Just at a guess, I'd say only 10 to 20% of us will make it through this bottleneck. And in the process the ecosystem is going to suffer a lot as well.

The planet won't support even a few hundred million people as hunter gatherers, it never did, even before agriculture. So those who survive will do so by farming, on a much smaller part of the available land than we currently use, leaving the rest of the planet to recover from what we are currently doing to it.

@ Steven B Kurtz

Hmmm, no free will, eh? Sound like a good excuse not to try to change the way things are going. I don't buy it. I feel like I have free will. Daniel Dennett, my favourite philosopher, seems to come down on that side of the argument, so I intend to continue behaving as if I do indeed have free will. That is, making choices which can make a difference, rather than giving up and enjoying the ride down.

Are humans different from other animals? I'd say yes, in that our intelligence and our abilities to use tools to manipulate our environment gives us a chance to anticipate changing conditions and adapt to them.

Something like voluntary simplicity is no doubt the answer to over consumption, that and/or dieoff (probably less than 100%). And those who are prepared have a much better chance to make it through the bottleneck we face. It's still not a sure thing, of course.

The religions you mention may well breed faster, but they are also dead organizations walking. The Christian churches where I live have a lot of empty pews, and the ones that are full are full of old people--very few families with children. It seems that a lot of North American and Europeans are concerned about the influx of Muslims, and the effect this will have on our culture. But the older generation of Muslims are also worried about losing their young people to European culture, which I think is the more realistic concern.

I met Dennett a few times while taking grad courses in Philosophy at Tufts nearly 20 years ago. He is a "compatibalist" which is one thing upon which we disagree. He is a determinist, but wants to proceed 'as if' we have free will. My challenge to him and you is to provide evidence for *anything* that is not physical or inextricably tied to it. (energy-matter-information) If you do so, a Nobel Prize likely awaits!

Heredity, plus the cumulative effects of experiences since conception, are embodied in us. (all life forms similar) When we encounter the 'present', the two combine to *cause* the outcome. Please tell us about any other drivers!

Voluntary simplicity is a tiny exception to the Maximum Power Principle. Every day increasing numbers of people are INvoluntarily simplistic. (billions) Canada is in the top handful of countries for quality of life. Yet increasing energy throughput is the rule. This will better explain:

https://www.ecologycenter.us/ecosystem-theory/the-maximum-power-principle.html

I'd love for a sterility virus to emerge which is effective only on the superstitious. My sci-fi dream! ;-)

@ Steven Kurtz

It would be kind silly for a guy like me, with only a highschool education, to argue with you. I gather you have a doctorate in philosophy. So I won't. But perhaps a friendly discussion would be OK.

I had a quick look at the link you have quoted two or three times now. In the light of this, what do you think about collapse? And the chances of adapting to it? I guess we agree that there is no chance of stopping the process.

By the way, my point I was trying to make in this blog post was that the people who are practicing involuntary simplicity are not the problem. In my next two post I'll be talking about why the rest of us consume so much. You, it seems would attribute that to the "maximum power" law, but I think there is a lot more too it than that.

@ Irv,

I misunderstood certain aspects of the ecological footprint as determined by the Global Footprint Network organization. I apologize for not researching it more thoroughly earlier.

I looked through the definitions found at the link you supplied. Yes, a “global hectare” is a unit of area as adjusted for productivity and waste absorption ability. Desert and ice caps have very little productivity, so their adjusted area is very small even though the actual area may be large. This means that the total of “global hectares” does not match the surface area of the earth but is rather a synthesized surface area.

The earth has about a 51-billion-hectare surface area, so the "global hectare" total of 12 billion is only about 25% of the actual area, a little less than the earth's total land area but much more than the non-ice-covered land. So, the current total global hectares do have a rough relationship to earth’s useable land area plus an area of ocean with similar total productivity, but they do not refer to the average productivity of an actual hectare on the surface of the earth.

It is somewhat confusing when publications talk about the ecological footprint of humanity. They talk about 1.65 to 1.73 "earths", which many people, including myself, thought referred to the actual earth, rather than the total number of “standard productivity” hectares on the earth.

It would be simpler if they just adjusted the per capita earth-area requirement as the three parameters of land productivity, human population and human consumption changed, rather than adjusting the number of global hectares for productivity changes and then also adjusting the per capita hectare requirement as population and consumption change. As the carrying capacity of the earth deteriorates people needing more land to live is a pretty simple concept to understand.

In any case, they have decided to convert the productive capacity of the earth to a unit of area, adjusted, as you point out, for average productivity. They could have just as easily converted productive capacity to a unit of weight, say tons, and apportioned them on a per capita basis, but then they wouldn’t get to use the word “footprint”.

One last comment. The Global Footprint Network folks define land “productivity” such that only products useful to humans are counted. This is why the total global hectares can change depending on what we humans do with the land. Arable agricultural land counts far more than pasture.

Based on their accounting methodology, the ecological footprint of hunter gatherers was quite large. Consider the hunter-gatherers in the Amazon. The total biological productivity of the Amazon rainforest is immense, and hunter-gatherers can make little impact on that, but the fraction that is useful to humans by hunting and gathering is very small. Thus, the land area needed for sustenance was quite large. According to the Global Footprint Network methodology discussed here, the primitive hunter-gatherers could have dramatically reduced their ecological footprint by cutting down the rainforest and engaging in intensive agriculture on the cleared land, which seems to me to be a perverse “benefit” of their accounting method.

Irv,

I enjoy your blog or I wouldn't be here. (determined by my history! ;-) I have no graduate degrees. PhDs were driving taxis in NYC when I quit NYU grad school in the early 70s.

There are myriad influences on consumption habits including advertising. Hierarchy is wired in social mammals, and status is part of mate selection. Sex is a powerful driver; and seeking security for the female and brood has been selected over hundreds of thousands of years. A tall, clever hunter has changed a bit in some societies in which money, confers power. But the desire for energy throughput is still at base.

You might enjoy this on free will:

https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/strawsong/

BTW, I'm a dual citizen having spent over 7 years in Ottawa. We returned for family reasons. (grandsons)

I'd enjoy meeting some day. I think we're similar vintage.

@ Joe Clarkson

I don't collect a pay cheque from the Global Footprint Network, but even so there are a few areas where my understand differs from yours, and I can't resist the urge to list them. Please don't take this personally.

1) The global hectare is NOT a measure of land area, but rather a measure of biocapacity. Yes, it is given in terms of average biocapacity per average hectare, and often global hectares for person, but it is important to remember that they are talking about biocapacity NOT land area.

2) Deserts, mountains and oceans where there are no fisheries are not included AT ALL in the total productive area.

3) The total area of bioproductive area is more than the non-ice-covered land because it includes bioproductive waters, i.e. those that we fish, and I suspect, those where there are sufficient quantities of phytoplankton to contribute to carbon capture.

4) The "global hectare" is used as a unit of biocapacity because weight (something like a "ton") is not a suitable measure for many of the things that biocapacity includes. While it is confusing, in the end it is simpler and more accurate to use global hectares. If we dug deep enough on their website I am sure we'd find table of the actual data the collect and use. I haven't managed to do this yet.

5) In addition to things like the products of pasture and cropland, biocapacity includes the products of fisheries and forests. One of the primary products is carbon capture, of which the human race currently "consumes" a great deal. The Amazon rainforest is in fact more valuable for its carbon capture capacity than it would be as cropland or pasture. The hunter-gatherers in the Amazon only use a tiny fraction of the biocapacity of the forest and accordingly their footprint is quite small, even though their tiny consumption is spread out over a relatively large area of land. If they were to cut down the area of forest that they currently use and become farmers their consumption, largely in terms of carbon released, but not captured, would be much higher. That is, their Ecological Footprint would be much larger.

The Global Footprint people publish a map which is coloured to show which countries are biocapacity creditors and debtors. As you can see, the countries in the Amazon basin, as well as those occupying the equatorial rainforests of Africa, and countries like Finland, Russia and Canada, which have large areas of untouched forest, are creditors.

The video on this page may make the accounting involved in the Ecological Footprint a little clearer.

I get the impression that you are not highly impressed with the work of the Global Footprint people, and in some ways I agree. The Ecological Footprint is only a measure of biocapacity and our consumption of that biocapcity. As such it leaves out many important things which are leading us toward collapse.

1) They don't look at non-renewables (fossil fuels and minerals) at all. Our industrial civilization is critically dependent on the supply of many non-renewable resources, for which there are no practical substitutes.

2) While they do look at biological capacity for carbon capture, they might do better to look at green house gas production as well.

3) They don't look at water use at all, but many of the sorts of biocapacity production that they do look at are dependent on the availability of water.

4) I can hardly believe it, but they don't look at biocapacity used by other species. It seems to me that if we continue converting the habitats of other species to human use, resulting in the extinction of those species, this will have large effects on the biosphere and its biocapacity. But the Ecological Footprint doesn't seem to account for this.

@ Steven B Kurtz

I just turned 67. I don't know how that compares to you, but at my age, a few years one way or the other doesn't matter all that much.

Even if you only have a Bachelor's degree, you've still spent a few more years in school than me. Though I would like to think I've learned a few things with all the life lived and all the reading I've done since I got out of school....

It is reassuring that you are enjoying this blog. I haven't quite know how to take some of your comments. When I haven't replied, you can chalk it up to that.

In my next couple of blog post will touch on the topics of advertising and hierarchies. I'll let you know in advance that I don't see hierachries as being wired into social animals, not our type of social animal anyway. Indeed much of our past was spent living in assertively egalitarian social arrangements, and that shaped us quite a lot. I know that having grown up in modern western society, this seems improbable. But many traits we take a "evolved in" are actually the result of relatively recent cultural changes.

I do agree with determinism, i.e. that events are determined by physical laws and humans are no exception to this. At the same time we clearly do experience free will and I think we have to proceed as if it is real.

Irv,

I will turn 68 in a few weeks so we compare in age. I have been following your blog for a few years now and find it thoroughly informative and enlightening (not sure if I have commented before?).

Although I certainly disagree with you on occasion I haven't felt it necessary to criticize as we are mostly on the same page (atheist, determinist, scientific).

I was an attorney in one of my employment incarnations (as was my wife). Even though when I was younger I thought higher education conferred some intelligence on the recipient, I no longer believe that. Clarity of thought and an ability to integrate novel information is what I prize in your blog. My personal experience has been that higher education generally leads to a rigidity of thinking, a greater investment in the status quo and a greater degree of denial.

I think the question of free will is up in the air. I think that the MPP principle argues for lack of free will. Also, I know that current experiments in neurobiology seem to support the argument that we don't have free will. BUT I'm not entirely convinced that we lack it (maybe that's just an emotional response?). I think proceeding as if we do is probably the best response.

Thanks for a great blog.

AJ

Irv,

I'm nearing 76. No big deal. Re hierarchy, I only know what I've read and observed. Even Kibbutz have hierarchy. There are degrees of expression depending upon the societal values and structure. I suggest you do a bit of research before forming an opinion. Like voluntary simplicity, egalitarian societies are rare exceptions to the extent they exist. None are purely so. Nature doesn't make us equal, and we can only pretend!

@ AJ (epicurean empiricist)

Nice to hear from you, and I think it is the first time. I'm certainly glad to hear you're enjoying what I've been writing here. It sounds like we share positions on a great many issues.

I'll leave free will to the philosophers, who don't seem to have anything better to do anyway. It feels like I get to make choices, and I am going to keep on trying to make the right ones.

I'll be interested to hear what you think of my next two posts in this series. They cover so areas I haven't touched on before.

@ Steven B. Kurtz

I have several friends who are in their mid seventies and find I get along with them quite well.

As with you, I only know what I've read and observed. Modern society is indeed almost universally hierarchical. But there seems to be a widespread consensus that before the advent of civilization, this was not the case.

From my own experience, I know many (including myself) who prefer to neither follow nor lead. Horizontal democracy and consensus decision making have much to be said for them, in my opinion.

In any case, you're going to have a field day with my next two posts. Stay tuned.

Post a Comment