|

| Weavers Creek Falls Harrison Park, Owen Sound, Ontario |

This is the fourth of several posts that I would have preferred to publish all at once, were it not for the extreme length of such a piece. It will make more sense if you go back and read the whole series, starting with the first one, if you have not already done so. Maybe even if you have already done so, since it has been months between each of the posts. For those who don't want to re-read the whole series, and since this is the last post, I'll summarize somewhat less briefly than I did in earlier posts. If you want to skip it, click here.

Overpopulation and overconsumption (and their consequences) are the most serious problems that we face today. Overpopulation is going to take decades to solve, while overconsumption could be addressed quite quickly if certain obstacles could be gotten out of the way. By reducing our level of consumption, we could reduce our impact on the planet and give ourselves time to reduce our population.

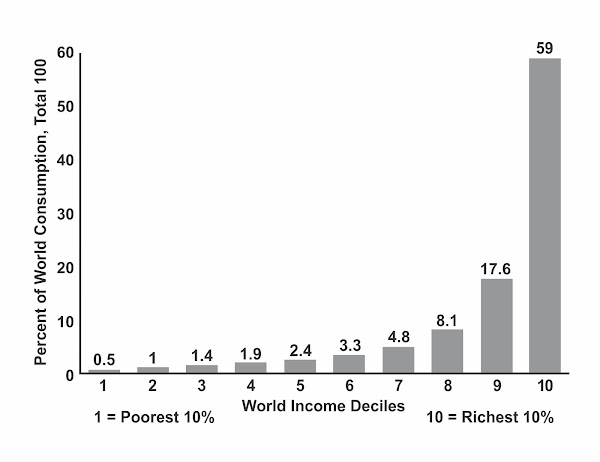

The blame for overconsumption can be laid squarely at the feet of capitalism, with its insatiable hunger to accumulate wealth, its inescapable need for endless growth, its inability to tackle any problem that can't be solved by making a profit and its endlessly blaring marketing machine which convinces us that we must consume, consume, consume. It is important to note that the majority of that consumption is done by a minority of people, the top ten to twenty percent of the richest people in the world. Sadly, I am part of that group and I suspect that many of my readers are as well, even though we wouldn't call ourselves "rich".

Many would lay the blame at the feet of individual people who are greedy, weak and undisciplined. I would say that if you take away the influence of capitalism, you would hardly recognize those people, and they would no longer be causing consumption problems. Solving them, more likely.

In a previous post where I looked at the problems with industrialization, I promised to have a more detailed look at our financial systems and our governments.

In this new series (Time for Change) I am finally doing that.

In Part 1 we looked at our financial system and saw that money is a tool that facilitates the accumulation of wealth by capitalists, and a mechanism by which they control the rest of us. It does this by making it possible to keep score in the complex game that is our economy, and pretty much guarantees that the wealthy win. Unfortunately, our financial system creates money as debt, which must be paid back with interest. In order to do that, the economy must continually grow or it will collapse. At the same time, the inevitable consequence of continued growth on a finite planet is also collapse.

But we can do without money and more importantly without keeping score. We need to get rid of money, the financial system and capitalism, and replace them with a system where each of us contributes according to our abilities and receives according to our needs, without keeping track of who is ahead or behind.

If this sounds like some sort of communism, you are right and that is exactly what we need. But anarchistic communism, rather than the autoritarian communism of the twentieth century.

In Part 2 I discussed the problems with hierarchies, especially with capitalism co-opting governments. The point being that hierarchies and capitalism are potent, and mutually reinforcing, agents of overconsumption.

For my purposes here, a hierarchy is an organization divided into different levels, with direction and co-ordination flowing down from above and wealth flowing up from below. A hierarchy is built like a pyramid, with many people at the bottom and only a very few at the top. There are serious problems with this way of organizing a society.

Like money, hierarchy is a tool designed for the benefit of certain people (those at the top), to be used by them to secure their power, wealth and privileges, and to keep the rest of us in the position where we "belong"—lower down in the hierarchy. In the process, we are prevented from ever realizing that there is any viable alternative. Our civilization is so big and complex only because it has to support hierarchies. If we didn't have to maintain hierarchies for the benefit of those at the top of them, we could adequately take care of ourselves with much simpler organizations, in smaller groups, at less expense—in other words, with less consumption. I usually refer to this phenomenon as the "diseconomies" of scale—the opposite of economies of scale. Economies of scale do exist, of course, but beyond a certain point the organizational costs swamp out the advantages of size. And that point is surprisingly small.

In Part 3 I asked three questions:

1) Are human beings naturally hierarchical? Are we doomed to drift back into a hierarchical organization even if we successfully get rid of today's hierarchies?

In brief, while it is easy for human societies to fall into the hierarchy trap and suffer for it, we evolved living in small egalitarian groups and have many adaptations which make us good at that way of life and also make it good for us.

2) Are there viable alternatives? That is, are hierarchies necessary when we organize ourselves into large groups and take on large projects, or are there others ways?

Hierarchies exist mostly for their own benefit, justified without really being justifiable, and the size of many of our endeavours is more a result of hierarchical organization than the needs of the actual work. There are other perfectly workable ways of organizing our efforts without hierarchies.

The owners, at the top of hierarchies, contribute very little that is of any real use, and most undertakings would work much better if owned by the workers and/or the people who consume their products. On the next level(s) down from the top, people are doing "coordinating work", and I'll admit that much of it is necessary. But it could just as easily be done by the actual working people, as part of their jobs. This sort of self-management would work better, and result in a greater sense of ownership and empowerment for the workers.

I left my third question for today.

3) Given the strengths of today's hierarchies and capitalism, and their success at propaganda, is there any hope that we can get rid of them?

Now that we are aware that hierarchies and capitalism cause more trouble than they are worth and indeed are the main obstacles to solving our most serious problems, we are left with the task of getting rid of them. In other words, removing the people who are running the world today, and who are highly skilled at convincing us that this is the best possible world and that making any major changes would be a mistake. This appears, at first glance, to be a pretty tall order.

After thinking about this question for quite some time, I reminded myself that this blog is about the collapse of our global industrial civilization, or "Business as Usual" (which I will shorten to BAU in what follows). The hierarchies and capitalism I have been talking about are essential parts of BAU, and are collapsing along with it. Only in the context of that collapse is it possible to see what we should do about hierarchies and capitalism. It seems that collapse is going to take care of some of the heavy lifting for us. The devil, of course, is in the details.

The Collapse of BAU

It is critical to remember that collapse is not a singular event, but an on-going process. I have said it before, but it bears repeating—what we face is a continued slow, uneven, unsteady and unequal collapse with occasional recoveries along the way, similar to what we have experienced over the last few decades, but getting worse as we go along. This collapse has been going on since the early 1970s, and has a way to go yet.

By uneven, I mean geographically. This is a large planet and despite the interconnectedness of our current system, it is not all going to fall apart at once. Even today, we can see that some areas are suffering greatly, while others continue on as if nothing much is wrong. Of course, as time passes, more areas will suffer and fewer will be left untouched.

By unsteady, I mean chronologically. Collapse goes in fits and starts, with periods where nothing much changes and even occasional partial recoveries.

By unequal, I mean that collapse affects those of different social classes differently. For the most part this means that the lower classes will suffer more from collapse, but it is not always necessarily so. The lower classes have lots of experience in dealing with difficulties—collapse is really just more of the same old shit for them. For the upper classes, such difficulties are new and they are lacking in the skills and mental preparation to cope.

Many people are in a state of denial about collapse. As the process continues, more people will have the opportunity to experience it personally or at least see it taking place nearby, and realize that it really is happening. Many will gain experience coping with temporary failures of infrastructure, supply chains and the financial sector. This will provide motivation to prepare not just by stocking up on supplies and tools, but by networking and starting to build the communities that can eventually replace the current system.

It might seem that the easiest way to get rid of hierarchies and capitalism would be to just let the present system collapse and then step in to build a better one. It's not quite that simple, though. Currently, BAU supplies us with the necessities of life, not because that is a good thing to do, but because it has been a good way to make a profit. It is certain that as the system continues to collapse, this business sector will become less profitable even as prices increase beyond what most people can afford. Capitalism will gradually abandon it, leaving more and more people to their own devices. If we just wait for BAU to collapse, we'll likely starve and freeze in the dark while we wait.

What to do about collapse

Clearly, that is to be avoided. What you want to do is to wait until the local system has collapsed far enough that it doesn't have the wherewithal to successfully oppose you, but you still have the resources to build something to replace it. Of course, you'll want to replace it with something that can function autonomously from the system that is falling apart around it, and works "better" than that system. In some cases, your local government will actually be helpful and support a smoother transition. In other cases, they will hinder you and may even have to be opposed violently.

In any case, while you are waiting you shouldn't be idle—there are many useful things you can do.

A while back I wrote a whole series of posts on preparing for/responding to collapse. Naturally, I would suggest that you read it, but there are some specific elements of such preparation that I want to look at in more detail here.

The first is to get a head start on building the community that you'll need to replace BAU. By that, I mean the organizations like solidarity networks, mutual aid societies and so forth. A large part of that will be learning how to make them work and how to function as an individual within them. We currently live in a society where toxic individualism is rampant and we have been brainwashed to think that no other way of life is possible.

Whatever they have told you, things like co-operation, mutual aid and direct democracy are all powerful ways for people to organize themselves and reduce their dependency on BAU. In groups that practice mutual aid, everyone ends up doing better than they could have individually. Even the strong and skillful, who do not perhaps need as much help as others, still end up better off than they would have without the group. Yes, they will likely end up doing more than some of the other people involved—but still less than what they would have had to do by themselves.

And yes, there will be a few who will take advantage and arrange an easy ride for themselves, but in the small groups where mutual aid works best, it is pretty obvious when someone is slacking off. Shame is an effective tool to encourage them to contribute and most will either mend their ways or leave. The cost of supporting the very few who don't is not nearly enough to outweigh the benefits of being part of the group.

To succeed, such community building efforts need to be based on clear and present needs. If you're living in an area where collapse has not yet struck, where BAU is still "working" fairly well, then trying to put a community together because you think it will be needed someday isn't going to work. Those involved (including you) simply won't have the motivation to make it work, to stay together, when there are easier alternatives all around you. Especially when that community is made up of people who haven't yet had much practice at such things. A quick look at the history of intentional communities will show how hard it is to succeed at this.

So first, take every opportunity to work, and play, with people in your community. Build a network of friends and acquaintances. Get a reputation for contributing, reciprocating and carrying your weight. Then, when the need arises, you can get together with people you already know and respond more effectively.

Many kollapsniks recommend withdrawing from our present society, but I would suggest just the opposite. You should be socially and politically active. Ideally, you want to live in a society which will collapse as gently as possible, providing a solid social safety net and encouraging and supporting your community building efforts. You need to work to ensure that the society you are living in is as much like that as possible.

In my opinion, such societies are on the left side of center politically. An example would be the contrast between Pierre Trudeau's government back in the day here in Canada encouraging and actually subsidizing housing co-ops versus the red state city in the U.S. that has recently made having roommates illegal. My point being that better governments will welcome efforts by people to be self sufficient, and will set things up to make it easier to do so.

Progressive social democracies do their best to help oppressed minorities and will do a better job of supporting all their citizens as things get worse. They will be easier places to practice mutual aid. They will also be more willing to abandon BAU to at least some extent as it malfunctions more and more. This will include reducing the burning fossil fuels, reducing carbon emissions, reducing the amount of damage we are doing to the biosphere and changing the way we use materials to conserve dwindling non-renewable resources as much as possible.

Societies on the right side of center will do everything they can to keep BAU working for as long as possible, regardless of the consequences, and to maintain capitalism's control over working class people, preventing us from gaining any degree of independence and from building our own organizations. These regressive, conservative societies are much easier to fall out the bottom of and will actively discourage groups coming together to practice mutual aid. And because they will also stick rigidly to BAU for as long as possible, they will do a good bit of damage in the process, ensuring that collapse is deeper and harder than it needs to be.

Such societies promote the traditional working class to the petit bourgeoisie, so that they come to identify with the upper classes, seeing themselves as "temporarily embarrassed millionaires" who are not interested in solidarity with other working class people. This results in behaviors that are clearly against their own best interests, especially when it comes time to vote. They are willing to go as far to the right as it takes to protect their perceived entitlements. Ironically, modern business unions are also part of this regressive effort.

The result is an almost universal drift to the right politically—exactly the opposite direction from what we would prefer. A big part of our work will be to oppose that drift.

As times get worse, people look for politicians who can promise them some relief. Right wing politicians are always ready to do this, and as their promises do not involve giving up on BAU, or even any change in our lifestyles, they are popular at election time. I predict that we will go through a few more decades of rightward drift, ending up with outright fascism in many cases. Indeed this trend will be a major part of the collapse of our societies, since those right wing politicians won't be able to keep their promises, if they ever intended to do so in the first place. We need to be very suspicious of politicians offering easy solutions.

Of course, we have already tried fascism—really tried it—and it really didn't work. Read up on the history of Germany, Italy and Spain in the twentieth century. I don't expect it will work any better this time around when the underlying problems are considerably worse than they were a century ago. The right wing regimes will weaken and people will eventually rise up to get rid of them. Sadly, there will be a lot of suffering involved in this process. However, when it is over, another generation will have seen up close what's wrong with right wing politics and fascism in particular and will refuse to give such ideologies even a moment of their time. Really though, we could save ourselves a lot of trouble if we could avoid being fooled by the "rightists" in the first place.

Collapse will be less destructive in those places that started out further to the left, and managed, at least to some extent, to stay that way. Based on what I've just said about right and left wing governments, it is tempting to look ahead to a future consisting of one of two extremes:

1) People become more aware of what is happening and insist on change, leading to a soft and controlled decline, with a smaller population and a lower rate of consumption that is within the planet's carrying capacity. Not much more damage would be done to the biosphere than we have already done and not too many more non-renewable resources would be used up, leaving the world a more survivable place. Unfortunately, this seems improbable, as most of the people who are currently running things will fight it every step of the way.

2) We refuse to accept that the system isn't working and put every effort into keeping BAU going until the very last possible moment, resulting in a deep, hard collapse which will wipe out most of mankind, do far more damage to the biosphere than option 1 and use up even more of the remaining non-renewable resources. This sort of collapse would be much harder for any survivors. Sadly, it seems quite likely.

I am always suspicious, though, when situations are framed in terms of two irreconcilable extremes. This sort of polarized thinking blinds you to many other possibilities. A great many (and more realistic) futures lay on spectrum ranging between those two extremes, and even on spectrums that run between different points altogether and in different directions.

Not all people are helpless (far from it), nor are they incapable of imagining different and better ways of living. I think it is important to allow dissensus, letting people hold different opinions and try different things. We should agree to disagree, and wish each other well along the way, even offering to help when it is to our mutual advantage. Then we can observe what does and does not work. Realistically, many people will get their timing or their organizations (or both) wrong, and will have a much harder time of it than needs be. Others will do better, and in the process, they will learn a great deal. That is, perhaps, the best we can hope for.

Some people, of course, won't be willing to go along with dissensus, and will try to force the rest of us to see things their way and do what they want. Such folks, if they take their shenanigans far enough, are worthy of our active opposition. Even so, the fast and violent collapse you read about in collapse fiction is just that, fiction. While it certainly makes for thrilling stories, it's not very realistic. We just won't have the resources available to spend on extensive conflict.

What I've been try to point out in these last few posts is there are many things that we have tried repeatedly and that just don't work—hierarchies, capitalism and money to mention just a few. We'd be best to leave them on the junk heap of the past and carry on with things that we know do work—solidarity, co-operation, mutual aid, direct democracy, self management and community ownership of resources.

Some people would suggest taking action to help speed up collapse. I do NOT think this is a good idea. It would mean doing actual harm, and that harm will be felt most acutely by those at the bottom of the heap, who are already suffering more than the rest of us.

There is always more to say, but I think this would be a good place to wrap up this set of posts. At one point I promised to talk about the third item in the I=PAT equation—technology. When I finally get inspired to write about that, it can go in a standalone post and doesn't need to be tacked onto the end of this series.

The other thing I have been thinking about is writing some fiction. I have not written any fiction since I was in high school (50 plus years ago), so it would be nice to give it a go again. Story telling is a big part of human communication, and might serve as a better way of getting across some of the ideas that I'd like to share.

During the last couple of years I've been reading a number of very interesting books and websites, which bear upon what we are discussing. Here is a list of these, along with a few that I've read previously, but that also have been a help.

Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next), by Dean Spade

Mutual aid is the radical act of caring for each other while working to change the world.

Fascism Today: What It Is and How To End It, by Shane Burley

A detailed map of the far right and a game plan for building the mass movement that will stop it.

We can no longer ignore the fact that fascism is on the rise in the United States. What was once a fringe movement has been gaining cultural acceptance and political power for years. Rebranding itself as "alt-right" and riding the waves of both Donald Trump's hate-fueled populism and the anxiety of an abandoned working class, they have created a social force that has the ability to win elections and inspire racist street violence in equal measure.

Fascism Today looks at the changing world of the far right in Donald Trump's America. Examining the modern fascist movement's various strains, Shane Burley has written an accessible primer about what its adherents believe, how they organize, and what future they have in the United States. The ascension of Trump has introduced a whole new vocabulary into our political lexicon—white nationalism, race realism, Identitarianism, and a slew of others. Burley breaks it all down. From the tech-savvy trolls of the alt-right to esoteric Aryan mystics, from full-fledged Nazis to well-groomed neofascists like Richard Spencer, he shows how these racists and authoritarians have reinvented themselves in order to recruit new members and grow.

Just as importantly, Fascism Today shows how they can be fought and beaten. It highlights groups that have successfully opposed these twisted forces and outlines the elements needed to build powerful mass movements to confront the institutionalization of fascist ideas, protect marginalized communities, and ultimately stop the fascist threat.

Debt, The First 5000 Years, by David Graeber

Hierarchy in the Forest: the evolution of egalitarian behavior, by Christopher Boehm

The Art of Not Being Governed, by James C. Scott

Against the Grain, a deep history of the earliest states, by James C. Scott

Living at the Edges of Capitalism: Adventures in Exile and Mutual Aid, by Andrej Grubacic

The Dawn of Everything, by David Graeber and David Wengrow

No Bosses: A New Economy for a Better World, by Michael Albert

Balancing Two Worlds: Jean-Baptiste Assiginack and the Odawa Nation, 1768-1866, by Cecil King

- Review of Balancing Two Worlds, on the Manitoulin Expositor website.

- Wikipedia article about Jean-Baptiste Assigninack

- Buy Balancing Two Worlds, from the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation.

Websites

- Seattle Solidarity Network

- Seattle Solidarity Network on Facebook

- Seattle Solidarity Network on libcom.org

- Microsolidarity

- Hierarchy Zoom Bombed

Links to the rest of this series of posts:

Collapse, you say? / Time for Change

- Collapse You Say? Part 1, Introduction, Tuesday, 30 June 2020

- Collapse, you say? Part 2: Inputs and Outputs, Wednesday, 30 September 2020

- Collapse, you say? Part 3: Inputs and Outputs continued, October 7, 2020 /li>

- Collapse, you say? Part 4: growth, overshoot and dieoff, January 2, 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 5: Over Population, January 8, 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 6: Over Population and Overconsumption, Februrary 21, 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 7: Needs and Wants, Human Nature, Politics, March 8, 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 8: Factors which made industrialization possible, May 13 , 2021

- Collapse, you say? Part 9: Unintended Consequences of Industrialization, May 20 , 2021

- Collapse You Say? Part 10/Time for Change, Part 1: Money, January 5, 2022

- Time for Change, Part 2: Hierarchies, Februray 16, 2022

- Time for Change, Part 3: Without Hierarchies? April 23, 2022

- Time for Change, Part 4: Conclusions June 22, 2022