Allan Harper, later on Tuesday, April 9, 2030

Allan Harper left the old farmhouse and walked across the yard to the big pole barn where they'd been piling everyone's stuff as it came in, ready to be sorted out and distributed. It was getting dark, but a "dusk to dawn" light on a wood pole illuminated the area, and he easily made his way to the person-sized door in the east wall of the building. Entering, he called out, "Dad, you in there?"

"Yeah," Tom replied, "I'm back this way."

Allan picked his way between piles and found his Dad seated at a table which held an elderly desktop computer and a big printer. Behind him were several tables of seedlings with grow lights above and heating pads underneath. Tom had been working on them for the last few weeks—the pole barn was not, strictly speaking, heated, but it had been a warm spring thus far and the plants were doing well.

He nodded to his father and said, "I guess I owe you an apology."

"Maybe so," said Tom, turning away from the computer so he could face Allan. "I gotta tell you that 'fascist' shit cuts pretty deep."

"Yeah, I can see that," said Allan. "So, sorry. But...well, a lot of what you say really does sound fascist to me."

"I am puzzled by that," said Tom, "I've spent a lot of time, on my blog and on social media—even in person, sometimes—helping people identify fascism and talking about what is wrong with it. As I understand it, the two essential things about fascism are: one, a belief in inequality, that some people are significantly better than others, and we would do well to let those superior people lead, and two, that there is an essential identity, often based on race, that characterizes that elite. Right?"

"Sure," said Allan, "no argument there. But there are other elements to fascism, and eco-fascism is one of them. Whenever you start talking about over population as the world's main problem, you set off my 'eco-fascist' detector."

"I think there must be a little more to it than that," said Tom. "Eco-fascist are by definition right wing, which I am certainly not, and they are against immigration, which I am also not. As I was reading just now on Wikipedia, they 'embrace the idea of climate change as a divinely-ordained signal to begin a mass purge of sections of the human race', which I certainly don't agree with."

"So you say," said Allan, "but then you go on and make a liar of yourself."

"How so?" asked Tom, with a puzzled look on his face.

"Well," replied Allan, "you brought up the ideas of carrying capacity and overshoot—overshoot by 170%, I think you said—which implies mega, or maybe even giga, death, and mainly in the third world countries. All very handy for an eco-fascist, who would love to see all those poor, brown people gotten rid of. Environmentalism through genocide, it's been called."

"But I don't think overpopulation is our main problem," said Tom. "And I am not suggesting that we get rid of anyone. Maybe you need to look at little deeper into what I really am saying. Will you give me a chance to explain?"

"Sure," said Allan, "go for it. And you can start with this thing about overpopulation not being the problem—it's seems to me that it follows obviously when you start talking about carrying capacity and overshoot."

"Well, I've met a lot of people who do indeed think that connection is obvious," said Tom, "but I'm not one of them. I think you and I need to talk more about carrying capacity, but first we need to consider the other side of the calculation—the idea of impact. If our impact on the planet is greater than its carrying capacity, then we are in overshoot. Impact is the product of three factors: population, affluence and technology. I=PAT. Affluence, which is equivalent to consumption, is, in my opinion, the thing we should be focusing on. Overconsumption rather than overpopulation."

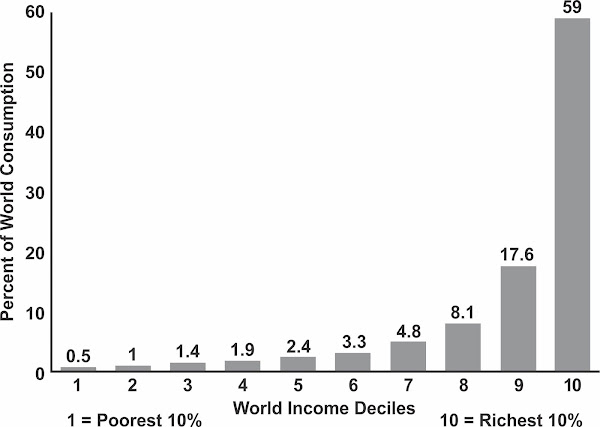

Tom reached back toward the table and picked up a sheet of paper, which he passed to Allan. "That's a diagram that I've been using as my banner on Facebook for years. I think it sums up some pretty significant information."

"OK, let's see," said Allan, "this plots percentage of total world consumption against income divided into deciles."

"That's right" said Tom, "see anything significant?"

"Well, it looks like the top decile—the richest 10% of the world's population—are doing almost 60% of the consuming," replied Allan, "and at the other end, the poorest people are consuming very little."

"Exactly," said Tom. "So if we did as the eco-fascists recommend—got rid of, say, the poorest half of the people living today—what effect would that have on our degree of overshoot? To make that easier for you, I've added it up—the poorest half of us only do about 7% of the consumption."

"Well," said Allan, pulling his smart phone out and starting up a calculator app, "if we are really 170% into overshoot, then reducing consumption by 7%... that's .93 times 1.7... we'd still be 158% or so in overshoot. Considering you're talking about killing over 4 billion people, it hardly seems worth it."

"I'm not talking about killing anybody, but yes, that's my point exactly," said Tom. "Here's another suggestion though—instead of killing anybody, let's try taking the richest 20%, who do nearly 77% of the total consuming, and reducing their consumption by 60%, so they are only consuming at a level that equals about 31% of our current total consumption. This still leaves them doing more than their share of consuming, which they seem to think they are entitled to, even though the other 80% of the population are only doing 23% of the total consumption.

"I've done the calculation, and it brings us down to around 92% of carrying capacity. In other words, not in overshoot at all. That's what an eco-socialist, or a green anarchist like me, thinks we should ideally do. And then we should put a quite a bit of effort into rebuilding our damaged biosphere so as to increase its carrying capacity and give ourselves a comfortable margin to work with. Of course, the 'them' I'm talking about is actually 'us', and that makes it harder."

"I have to admit," said Allan, "that even though you are discussing carrying capacity and overshoot, you don't sound much like an eco-fascist. At least when you are given a chance to go into the details."

"Funny how that works, eh? But I agree, many people in the 'collapse sphere' do deserve to be called ecofascists," said Tom. "They make statements about needing to 'get rid of' a certain number of people to solve the overshoot problem. Then they start talking about how even poor people contribute to overconsumption and how we need to stop the developing world's population from growing so fast. Without even considering that consumption in the developed world is growing faster than population in the developing world. On top of all that, it's clear that these folks have no intention of doing anything about their own contributions to overconsumption or overpopulation."

"Yeah, and it's that kind of thing that gets me pissed off," said Allan.

"And so it should," said Tom. "But a moment ago you said 'if we're 170% into overshoot'. I take it you're questioning that number?"

"More the carrying capacity numbers that it is based on," replied Allan.

"Right," said Tom, "and you were saying something about the whole concept having been debunked?"

"Yes, exactly," said Allan. "As I understand it, carrying capacity is dependent on technology—with better tech the planet could support more of us. It's the T in your I=PAT equation."

"I'll get back to technology in a moment," said Tom, "but first there is an ideological issue that may be causing some confusion here."

"What's that?" asked Allan.

"Well, I've noticed that conventional leftist these days freak out whenever they hear anyone talking about limits," replied Tom. "As I was saying earlier, they think shortages are always fake and just created to keep prices up and profits flowing. I won't deny that does happen sometimes—the so called 'free market' is anything but. Anyway, they do allow as how we live on a finite planet and someday we may run into limits, but surely not yet. I think they are fooling themselves more than anybody else—we are clearly running into some real limits."

"You're really sure about that, are you?" asked Allan.

"Yes, I am," said Tom. "I've observed that among the general population there seems to be a lot of selective blindness and denial where this subject is concerned. As if there has always been enough and always will be, and that's the end of it. But the whole science of ecology doesn't agree. Carrying capacity has proven to be a very solid and useful concept. Sure, it isn't a fixed number—it's actually easiest to calculate afterwards, based on observations, and it varies from year to year responding to factors like rainfall, temperature and so forth. And you are right—it can change based on the sort of technology you are using, but whether technology makes things better or worse is a tossup. I'll give you some links to the organizations that are calculating carrying capacity and ecological footprint. See for yourself if they are full of shit or not."

"I guess I should do that," said Allan. "I do know that most 'conventional leftists', as you call us, think that only the top 1% or so need to reduce their consumption, and then we can increase the standard of living of the people at the bottom end to something more equitable."

"That's a laudable goal," agreed Tom. "Those folks have a lot of faith in technology actually increasing carrying capacity and/or reducing our impact. Look up 'eco-modernism' if you want a catch phrase to match your 'eco-fascism'".

"Those eco-modernist guys have some good ideas," said Allan. "Right now we are feeding well over eight and a half billion people and doing a better job of feeding the poorest among them than we were even a few years ago. That's mostly due to advances in technology, so I don't see why are you so against it?"

"That's easy," said Tom, "The modern agricultural technology you're talking about is hugely dependent on non-renewable resources. Every calorie that's produced uses up ten calories of fossil fuel energy in the process. Plus minerals like phosphorous and potash, among others. All of which are non-renewable and being used up faster every year."

"But renewable energy sources are growing exponentially," said Allan. "At least they were before the depression hit."

"You're right," said Tom, "but the amount of fossil fuels we're using has been growing as well. Remember when I first started talking about Peak Oil back in the late naughties? We were using about 85 million barrels a day back then. In 2028 we were using well over a 100 million, even with all the renewable energy sources we'd added. The depression has reduced energy use somewhat, but it has also reduced investment in renewables and discovery work for fossil fuels. The big oil companies are spending less every year on finding new resources and borrowing money to pay dividends to their stock holders. And it's been a long time since new discoveries exceeded consumption. Clearly this can't go on forever, even if the depression is giving us a bit of a breather.

"We've gone to the ends of the earth and surveyed essentially all the resources. New finds are getting rarer and smaller, and the quality of the resources being discovered is getting lower, taking more energy and fancier technology to access."

"We do have a lot of faith in technology, " said Allan, "I think it has a huge potential to fix our problems. I'm puzzled as to why you don't see that."

"Well, if you look at history over the last few hundred years, technological advances have always brought about increases in consumption, not decreases, by reducing the costs of goods and services and making them accessible to more people," said Tom. "We have a tendency to think of technology as something that creates energy. In fact, technology uses energy and raw materials, to a large extent non-renewal resources like fossil fuels and metals that can't be replaced. And it produces wastes that have to be dumped in sinks that are another finite resource. Like CO2 from burning fossil fuels accumulating in the the atmosphere and the oceans, causing climate change and ocean acidification. So on the surface it may look like it's helping, but in reality, not so much.

"The idea of decoupling, of developing technology that can maintain and grow our standard of living without having a negative effect on the environment, seems in reality to be nothing but a pipe dream. The T term in I=PAT always seems to be greater than one when you look at it closely. I think technology has an important role to play in our future, as you'll see here if things go as I'm planning. But we are going to have to be very careful not to use it in ways that make things worse."

"Technology saving our asses is a critical to my argument," said Allan, "and now you are telling me it's bullshit?"

"Sorry, but I am," replied Tom, "based on two things:

"one, so far we have achieved only a little bit of relative decoupling, that is, increasing consumption these days doesn't have quite the impact it once had, but we are a long way from absolute decoupling—from actually managing to increase our consumption while at the same time reducing our impact. And there's no clear path to get from here to there.

"And two, the current state of the world is not conducive to further technological development. Not right away, for sure. Currently the whole planet is mired in a pretty serious depression, there's no spare money for anything, and quite a few places are suffering civil unrest or outright war. Climate change is getting worse every year, new pandemics and new variants of the old ones keep popping up and sabotage of our energy infrastructure continues."

"OK, you got me there" said Allan. "I have to admit that, over the last couple of years, I have grown more pessimistic about revolutionary changes ever happening. Whether you're talking about social organization or technology. I had a lot of hope for nuclear fusion as an energy source that could save us, but now it seems like all the research projects are shut down due to lack of funds."

"Fusion would only have been a short term fix," said Tom, "solving the energy shortage only to run us up against other limits in the long run, and pushing us farther into overshoot in the process. Make energy cheap and the waste heat from our increased energy use would soon become a problem, along with shortages of material resources.

"Anyway, I reached the same conclusion about revolutionary change years ago. You really should read my series of blog posts that summarizes the book The Limits To Growth. Sure, the book was published in the early 1970s, and wasn't meant to be a prediction, but since then things have gone pretty much as they said they would if we didn't change from our 'business as usual' approach.

"As I've just said, we do need reduce our level of consumption, and the best way to do that would be to get rid of capitalism. This would significantly reduce the ridiculous overconsumption inherent in the lifestyles of the rich. It would also get rid of the production and consumption of unnecessary products and services needed to create profits so the rich can continue to accumulate wealth. This might not quite get us out of overshoot, but darn close. To get the rest of the way, we could eliminate some of the waste that's built into our system, and if all else fails, try practicing just a little bit of frugality.

"It's not going to happen, though... I expect that we'll continue right on as we are until collapse brings us to a grinding halt—reducing both population and consumption whether we like it or not—and by a lot more than is necessary just to get us out of overshoot. Some of the things causing collapse are consequences of overshoot—climate change in particular. Others are the inherent flaws in our capitalistic system finally catching up with us.

"All that talk with Jim about slow versus fast collapse," Tom said, shaking his head. "It'll happen at the speed it happens. Still, if we can mount some relief efforts, and help people adapt, I think we can slow collapse significantly and save a whole lot of lives. But if we let it get past a certain point, we'll no longer have the resources to do anything about it, and what follows will be a hard, fast collapse with very few survivors.

"Anyway, sorry for the rant. As you know, recently most of my efforts have been focused on adapting to the changes that are coming. Like setting up this place."

"I think I do follow your explanation," said Allan, "and since your focus isn't on eliminating poor brown people, I guess I can live with it. I do have a couple of questions that have been nagging at me for a while, though."

"OK, got for it," said Tom.

"The first thing is this," said Allan. "You been talking about reducing consumption and at the same time you been talking living well. I've been assuming both those things apply to the community you want us to build here, and it seems to me they are contradictory. What about that?"

"You're right in your assumptions," said Tom, "and on the face of it those two things are contradictory. But it seems to me that the capitalists have done everything they can to make sure a lot of our basic needs don't get fulfilled, while at the same time creating a bunch of artificial needs that they can profit from. So people feel they are missing something and spend a lot on consumer goods they've been told they need, but that don't really help. We are going to reduce that here, cutting off the endless marketing that we've all been exposed to, and at the same time doing a much better job of fulfilling our real needs. We should feel better while actually consuming less."

"OK, I think I see what you mean," said Allan, "and it may even work. It's a big change for us to make in how we live, though."

"Yes, it will be," said Tom. "I think you'll find it will be a positive change, though. Not having to worry about earning enough to pay the bills, having worthwhile work that clearly contributes to the community and free time to create our own entertainment and enjoy it with friends in that community, will make a huge difference."

"You know, I think it will," said Allan. "My other question is about sustainability. You haven't been using that word very much, but it is implied in much of what you're planning."

"Yes it is," said Tom, "and it's going to be harder than many of us probably think."

"Well, that's just what I was going to say," said Allan. "Even though we are going to be reducing our consumption, we'll still be dependent on a lot of non-renewable resources. What are you going to do when they run out?"

"Well, many can be replaced with renewable resources," said Tom. "Some quite easily and immediately, others not so much. We need to make those ones last as long as possible, giving ourselves time to find renewable alternatives, or ways of doing without."

"That does sum it up nicely," said Allan. "I just wanted to make sure you are aware of the problem and planning on addressing it. Sounds like you are."

"Oh yes," said Tom. "Those are both good questions. I am a little surprised, though, that you don't have reservations about the ethics of what we are planning to do here."

"How do you mean?" asked Allan.

"Well, we are setting up to live fairly well, while people suffer and die elsewhere," replied Tom

"You can't be expected to do the impossible," said Allan. "Under the conditions that are coming, the developing world, and for that matter, most of the developed world, might as well be on the moon. At least we won't be exploiting them or their resources anymore. And you're planning on significantly reducing our level of consumption, so we won't be taking more than our share locally—probably significantly less."

"That's true, but somehow it doesn't seem like enough," said Tom.

"OK, but didn't I hear you talking about helping pretty much everybody who shows up at our gate?"asked Allan. "And helping out the local communities as much as we can?"

"Sure, but..." said Tom.

"No buts," said Allan, "I think you've got that one covered, as ethically as needs be. But what's this nonsense you're talking about how we should organize this place?"

"What nonsense?" asked Tom.

"Well, based on the bits and pieces I've heard so far, I have to say I am not impressed," said Allan. "Leadership has got to be a pretty important part of any organization, and it seems that you want to do without it altogether. And you'd have us spend a huge part of our time in meetings, hashing out what we are going to do. But perhaps I should give you a chance to make yourself clear?"

"Once again, that would be nice," said Tom. "OK, first let's take a wide view and talk about how we ended up where we are today, organization wise."

"OK," said Allan.

"Earlier, I was talking about how our ancestors lived in egalitarian bands, and it worked very well for them," said Tom. "Nobody called me on it, but I said nothing about how that lifestyle originated. Our nearest primate relatives all live in bands dominated by a single alpha male, and it seems likely that we started out that way too. And stuck with it, up to a point."

"OK," said Allan, "what point was that?"

"Well," said Tom, "most of us have a built in resentment of being dominated. As our intelligence evolved we got to the point where we could imagine something better than putting up with a dominant bully, especially a bully who wasn't very good at his job. Our communication skills had also developed and we could share our thoughts on the matter with our fellows and make plans together to get rid of the bully. At first that might have been just to replace him with someone more agreeable, but if there were no volunteers we were left with the idea of treating everyone as equals and not having one dominant person. This worked so well that we stuck with it."

"But how did we get from there to where we are today, with hierarchies everywhere?" asked Allan.

"Well, eventually we started to live in larger groups," said Tom. "And they worked just fine, on the same egalitarian basis. But at some point, quite a while after that, a few people realized they could set up a hierarchy with themselves at the top and benefit hugely from opportunities this afforded for exploiting the rest of the population. They justified it by saying the larger group was difficult to manage and required a new, better kind of organization. By the time those at the bottom of the hierarchy realized they'd been had, those at the top had a firm grip on the situation. It was too late to do much about it—the rulers maintained a monopoly on force and violence. About all the common people could do, if they didn't want to go along with it, was to head for the hills. And many did.

"Today, we've all been fed propaganda about how hierarchies and leadership are necessary for efficient organizations, and many people accept that without question. But I think we can see that there are other ways of organizing groups, even large groups, other than feudalism or capitalism. Or feudal capitalism."

"And what specifically might those other ways be?" asked Allan.

"Well, I am an anarchist and an egalitarian," answered Tom, "and I believe strongly in direct democracy, based on consensus decision making. That all fits in well with the mutual aid, sharing and co-operation I was talking about earlier this afternoon."

"You know, Dad," said Allan, "you have a way of packing a whole lot of meaning into a few words. How about unpacking that a bit?"

"OK," Tom said with a wry expression on his face. "I guess that was a mess of buzz words that need further explanation. And some background on how I came to these ideas may be called for as well.

"Abraham Lincoln said that no man is good enough to govern another man without his consent. I would go further and say that no man is good enough to govern another man, period. I have worked for many bosses in large and small organizations, and none of them did a very good job of it. Sometimes that was partly the fault of the individual, but it was always the fault of the system as well. I have been a boss myself and I am no better.

"This isn't easy on the boss either—it's a stressful job. A good leader puts more into it, and it takes more out of him. When he finally packs it in, and he will, you are left with finding a replacement. Remember, I'm 75. Even if I am up to the job, and that's not certain, I've only got a few years left. I have no solution to any of this, except to change the system, and not put an individual in charge.

"To misquote David Graeber, one of my favourite anarchist scholars, 'To understand anarchy you must accept two things: one, that power corrupts and two, that we don't need power—under normal circumstances, people are as reasonable and decent as they are allowed to be and can organize themselves and their communities without being told how. If we take the simple principles of common decency that we already believe we should live by, and follow them through to their logical conclusions, everything will turn out fine.'

"This means that everyone involved must be treated as equal—that's egalitarianism. And direct democracy is when everyone in the community takes part in the decision making process, and decisions are made by discussing things until a consensus is reached."

"Doesn't this take a lot more time than having a leader who the rest of us just follow?" asked Allan.

"It does, somewhat," replied Tom. "but it also results in better decisions, using of all those spare brain cells that would be sitting around unused if we had a single boss, and benefitting from the knowledge and experience of everyone in the group. And when we go to implement the decision, we'll be working together with people who are already convinced that it's the right thing to do. No disgruntled minority working against what's been decided.

"Understand, I am not saying that every last detail must be hashed out in a meeting of the whole group. As I was saying earlier, crews will implement in detail the general decisions of the whole group and deal with the specifics of our day to day operations."

"You really think we'll end up with a net gain using this type of organization?" asked Allan.

"I do," said Tom, "lots of people have used it and with good results. There's another Graeber quote that explains what reaching concensus is really about, 'Consensus isn't just about agreement. It's about changing things around: You get a proposal, you work something out, people foresee problems, you do creative synthesis. At the end of it, you come up with something that everyone thinks is okay. Most people like it, and nobody hates it.'"

"OK, sounds good. But what about leadership," asked Allan, "don't we still need it in some situations?"

"Well, by now, I guess it's obvious that I'm not keen on the very idea of leadership," answered Tom. "I think we should be fiercely proud of not having leaders here.

"But, yes, I'll allow as how there as some situations where it might be beneficial. During emergencies, we should all be prepared to step in and lead if we find ourselves at ground zero—put out the fire, so to speak—then relinquish authority when things are well enough under control for a crew or the collective as a whole to consult and decide what to do long term.

"And there may be room for some different sorts of leadership. The same people who came up with those ideas on group sizes also talk about leadership as hospitality rather than domination. I'm not sure exactly what that means in practice, but it might be worth looking into. On the whole, though, direct democracy should be our thing. The only question is whether we are ready to give it a try. Or more specifically, are you ready?"

"I am still doubtful," said Allan, "but yeah, I'll give it a chance."

"Good," said Tom. "As it happens we have an individual among us who is a trained facilitator, and has some experience in assisting groups with consensus decision making."

"Who's that?" asked Allan.

"Angie Ferguson," replied Tom. In response to Allan's raised eyebrow, he went on, "yeah, I know—she introduces herself as a hair stylist, but before she ran out of money and dropped out of school, she was studying political science. She also took some serious courses on facilitating, and did quite a bit of work as a facilitator. I should have gotten her to help from the start today. When we go back to the house, I will invite her to facilitate the rest of our meeting. Get things going on a better footing, I hope."

"OK, I have to admit I am pretty clueless about this approach," said Allan, "maybe we could arrange for some training?"

"An excellent idea," replied Tom. "And now on to another issue."

Tom turned back to the table and picked up a 13"X19" sheet of glossy paper on which was printed a graphic and some text.

The Porcupine Refuge Co-operative

"What you got there, Dad?" Allan asked."Just an idea for a sign to go over our gate, including a name for this place," replied Tom

"Well, we sure as heck need a name," said Allan, "calling it 'this place' is getting lame."

Tom handed him the sheet and he looked it over. "Porcupine Refuge Co-operative, eh?" Allan said, "I get the 'Refuge Co-operative' part, but what's the connection with porcupines, and what's the graphic? It almost looks like a cave painting."

"It is a cave painting," said Tom, "and while there are various theories about what it means, the one I like best is that the guy on the ground with all the arrows sticking out of him—kind of like a porcupine—is an alpha male who just wouldn't take the hint when the other people in the band suggested that he move on. You can see that the others are pretty thrilled about doing him in."

"And this is a reminder to any individual who tries to set themselves above the rest of us here at 'Porcupine'?" asked Allan.

"You got it in one!" Tom said with a smile. "What do you think?"

"Looks good to me," said Allan. "I hope we can reach a consensus on it, eh?"

"Yes indeed," said Tom, "I hope so too. If you and I are good, perhaps we should head back and see if there's any supper left."

"I'm good, and hungry," said Allan. "Lead on."

When they got back to the house, supper was just finishing up. Karen sat them down at one of the big tables in the dining room, in front of plates of spaghetti and meat sauce. "I hope you two have got whatever it was out of your systems," she said.

"Yep," said Tom, "we're feeling much better now. Would you mind asking Angie to join us?"

"Yes sir," Karen said with a mock salute and headed for the addition. She was back in a moment with Angie.

"Hi Angie," said Tom, "I probably should have had you facilitating this meeting from the get go. Allan and I are all sorted out now and we'd like you to take over and facilitate the rest of the meeting. I need to finished my thoughts on ecology and then go on to the next section.

"Well, if all you are going to do is stand there and talk, maybe take a few questions, there won't really be much facilitating to do, will there?" said Angie.

"I'll grant you that," said Tom. "Not at the start, anyway. But I'm going to end up talking about participatory, consensus decision making. After that I'll introduce you. And then I have a suggestion that will spark our first bit of group decision making."

"I guess that might work," said Angie with a frown. After a moment's thought, she switched to a smile, and added, "OK, let's do it. What's this first decision about?"

"An idea for a name and logo for this place," said Tom. "You take over, give me a chance to make my suggestion and then I'll get out of your hair."

"Somehow I doubt that," replied Angie, "but sure."

"OK, we'll just finish eating and then I'll continue where I left off before."

A few minutes later Allan and Tom entered the addition. Allan took his seat at the back next to Erika, and watched Tom continue to the front of the room and pick up his marker.

"He get you straightened out?" Erika whispered in Allan's ear.

"Yeah, that's pretty much what happened," replied Allan.

"I hope you'll excuse the interruption," said Tom, "at least it gave you a chance to have supper. Anyway, I think Allan and I have our differences sorted out now. And he helped me get my thoughts in order for the rest of this."

Tom went on, going over all of what he and Allan had discussed before supper and, in Allan's opinion, doing a better job of making his points than he had the first time through. There were a few questions, but Tom fielded them all with no trouble.

"So, those are my thoughts on how we should run this place," said Tom. "I know I was never officially appointed boss around here, just sort of fell into by virtue of having started things, but at this point I am officially stepping down. This leaves us without a leader and better off for it. But a central role in participatory decision making is that of the facilitator. A facilitator is not a leader or boss, but more of a referee. And we are fortunate to have among us someone who is a trained and experienced in that role. I think you all know or at least have met Angie Ferguson. Angie, why don't you come on up here and take over from me."

Angie came to the front. Tom handed her his marker and then took a seat beside Karen.

"Maybe take over isn't exactly the right word, since I'm not going to be running things either," said Angie with a wink directed at Tom. "But I take your meaning. We really need to arrange some introductory training in this style of decision making for all of you, and also get a few more people trained as facilitators so we can share that duty around and avoid me becoming another de facto boss. We obviously can't do that tonight though. What we can do is discuss an issue Tom wants to bring up. Back to you, Tom."

"Thanks Angie," said Tom, standing up, but pointedly not resuming his former position at the front of the room. "I think we've all noticed that it's getting pretty awkward not having a name to call 'this place'. So, I have a suggestion."

He'd rolled up the big printout and brought it with him, and now he unrolled it and held it up in front of his chest. "The Porcupine Refuge Co-operative is my suggestion, and it comes with a graphic that I think we should paint on a sheet of plywood and mount above our front gate."

"Where the heck does 'porcupine' come from, and how does it relate to that graphic," asked Erika, "or to what we are doing here?"

Tom was a little thrown by this, and hesitated long enough for Angie to step in, "Bet you thought this would be easy, didn't you Tom?" she said with a grin. "You've already explained this to Allan, right? Just share with us what you said to him."

"Allan made it pretty easy on me," said Tom, "easier than his better half is doing, anyway. So, the graphic is a cave painting..."

Coming soon, The Porcupine Saga Part 7, When We Met Jack.

Links to the rest of this series of posts:

The Porcupine Saga

- The Porcupine Saga, Part 1: A Celebration at Porcupine, Allan Harper, July 21, 2040, published February 24, 2023

- The Porcupine Saga, Part 2: When The Lights Went Out, Part 1, Will Harper, Wednesday, July 19, 2028, published April 30, 2023

- The Porcupine Saga, Part 3: When The Lights Went Out, Part 2, Will Harper, Thursday, July 20, 2028, published May 16, 2023

- The Porcupine Saga, Part 4: One Last Lecture, Part 1, Allan Harper, early afternoon, Tuesday, April 9, 2030; published September 25, 2023

- The Porcupine Saga, Part 5, One Last Lecture, Part 2; Allan Harper, late afternoon, Tuesday, April 9, 2030; published October 12, 2023

- The Porcupine Saga, Part 6, The Sign Above Our Gate; Allan Harper, late afternoon, Tuesday, April 9, 2030; published October 12, 2023

- The Porcupine Saga, Part 7, When We Met Jack; Will Harper, late afternoon, Saturday July 21, 2040; Allan Harper, morning, Wednesday, April 10, 2030; published January 16, 2024

- The Porcupine Saga, Part 8, When We Met Jack, Part 2; Allan Harper, midday, Wednesday, April 10, 2030; published April 23, 2024